Galaxy versus Fantasy and Science Fiction

Theories of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Clifford D. Simak, Fredric Brown, Fritz Leiber, Damon Knight, Philip MacDonald, Fitz-James O'Brien, Oliver Onions, Winona McClintic and Margaret St. Clair.

Greetings and Salutations!

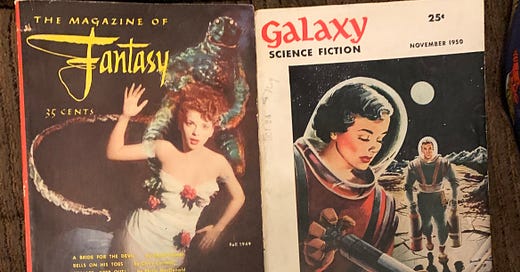

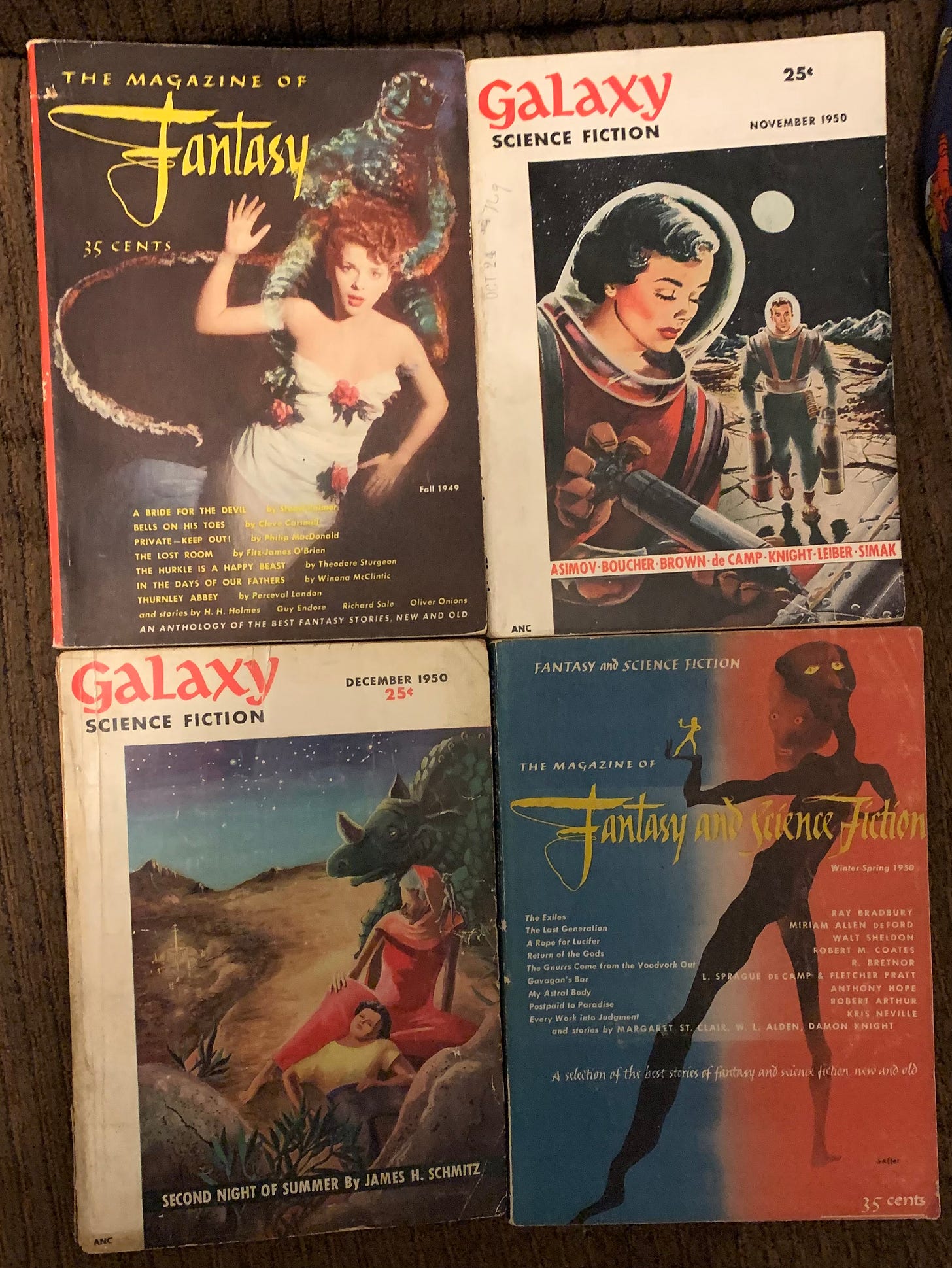

This Special Editon of The Official William Emmons Books Newsletter is to record my reflections on reading early issues of Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (F&SF). Last month I reviewed most of the contents of the first issue of Galaxy in one go here. I also reviewed some stories from the anthology The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction Third Series here (see review of “The Star Gypsies”) and here (see review of “Vandy, Vandy”).

In the first section of this post, I talk about my initial reactions to the magazines and my theories of science fiction and fantasy. This is followed by a discussion of the magazines’ self-conceptions and aesthetics. I close out this post with a look at some selected fiction from early Galaxy and F&SF issues.

Initial Reactions and Theories

My initial reaction is that I like both magazines. With the exception of one story, I’ve found everything in the first two issues of Galaxy at least interesting. My theory of science fiction is that it only needs to be interesting and concise to be successful.* If it is longer, then literary craft starts to become a virtue. And, of course, literary craft is always welcome.

By contrast, everything I have read from the first two issues of F&SF has been uniformly good. I think that this high level of quality is important because most of the magazine’s early stories are pure fantasy. My working theory is that fantasy has to actually be good to be successful.

Why the double standard? I am pretty convinced that good science fiction constitutes a literature of ideas. If the ideas are good or interesting, it can succeed even if the prose, plotting, characterization, etc. leaves something to be desired. By contrast, I am starting to convince myself that fantasy is a literature of emotional resonance, intrigue, suspense, titillation, adventure, and indeed the beauty of words themselves. All these things require literary craft.

This is not to say success comes easier in science fiction than it does in fantasy. In science fiction, there is no substitute for good scientific or philosophical ideas. One gets leeway in terms of craft. In fantasy, there is no substitute for craft. One gets leeway in terms of ideas and philosophy.

Three paragraphs above, I italicized the adjective “working” because I am still figuring this out for myself. I am curious if any of my beloved readers have feedback on my theories.

*My friend Jesse Willis of the SFFaudio podcast tells me I have stolen my theory of science fiction from him. He calls it his Lester del Rey theory and uses it to explain why he would rather read “The Faithful” than David Brin’s Sundiver or its sequels.

Self-Conceptions and Aesthetics

These early issues of Galaxy and F&SF show magazines that have different self-conceptions and aesthetics. Galaxy sees itself as a bona fide science fiction magazine for adults and publishes new stories in its genre most of which one could described as political, sociological or psychological. F&SF sees itself as a singular force in publishing for the kind of fantastic literature that the modern age has heretofore shunned. The editors pick old and new stories in their chosen field based on high literary quality seemingly without regard to whether they are fantasy, science fiction or horror.

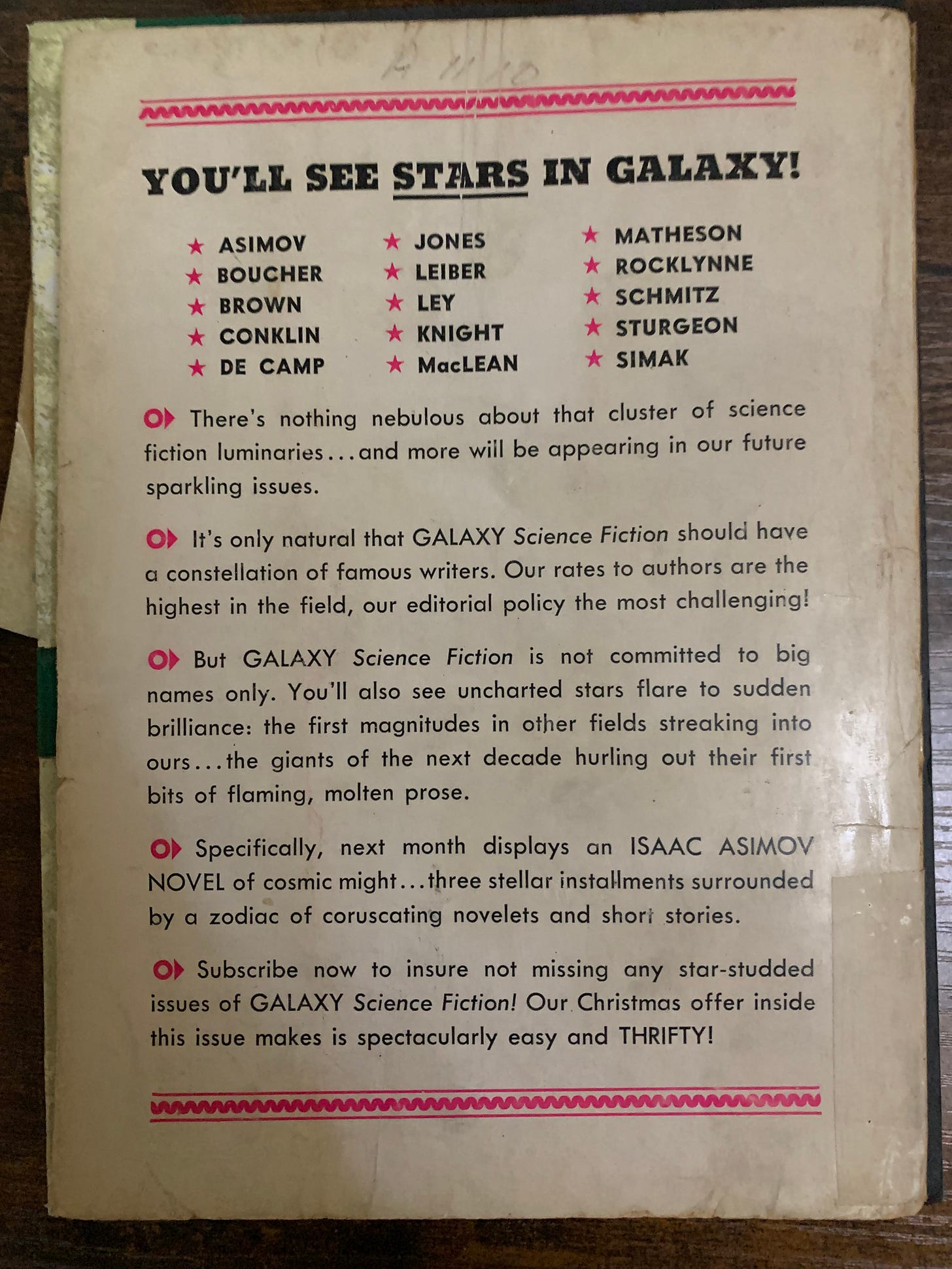

I have already written about how Galaxy’s first issue presents the new magazine as a mature one and differentiates itself from other science fiction rags that publish space Westerns and the like. The second issue continues along this track with a preamble from book reviewer Groff Conklin that states his job is to “propagandize for adult science fiction.” In an unsigned half-page section called Forecast, the copy reads that the magazine is not for the “mentally flaccid” and its fiction is designed to provoke a “cardiac, cerebral, and psychological” response in its readers. In the third issue, H. L. Gold’s editorial notes the magazine has the highest word rates in science fiction to attract the best talent, a theme elaborated on in the back page house ad pictured below.

Taking the second issue of Galaxy, dated November 1950, as an example there are three stories and a serial installment with political or sociological themes, a wonderful recursive time travel yarn (see review of “Transfer Point”), and a study in speculative xenobiology and alien psychology. There’s also a nonfiction feature by L. Sprague de Camp covering different geological theories of how continents work.

In the first issue of F&SF, dated Fall 1949 and for that single issue title simply titled The Magazine of Fantasy, opens with an introduction by publisher Lawrence E. Spivak stating that the fantasy field has been neglected in the 20th century. To remedy this, Spivak and his editors Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas proffer a magazine “featuring the best in imaginative fiction, from obscure treasures of the past to the latest creations in the field, from the chill of the unknown to the comedy of the known-gone-wrong. In short, the best in fantasy and horror.” (Emphasis supplied).

To put a fine point on science fiction’s omission from this statement, we should also draw attention to Spivak’s call for submissions a paragraph above the previously quoted text, “There is no formula. Just make your efforts to contradict the law’s of man’s logic—while adhering firmly to a freshly-created logic of their own.” (Emphasis in the original). This would seem to be an admonition against science fiction, at least of the left-brained Campbellian “hard” variety published in Astounding Science Fiction at the time. Though F&SF predates Galaxy by a year, it would also seem to preclude Galaxy’s “soft” science fiction.

That said, of 11 stories published in the inaugural issue, 2 were definitely science fiction and a third arguably was. Notably, two of these stories were more about affect than the scientific ideas in them. The third was a good and interesting political story. Naturally the other eight stories were fantasy and/or horror of various kinds. Two perhaps superficial differences with Galaxy were the use of reprints and the lack of a serial. Flipping through the issues of F&SF dated through the end of 1950, one sees these differences persist at least through Galaxy’s debut year.

I was very curious to pick up the second issue of F&SF, dated Winter-Spring 1950, and see if any explanation was given for the addition of “and Science Fiction” to the title. There’s no editorial or publisher’s statement suggesting a new direction or a clarification. The only nonfiction in the magazine is the book review section under the co-editors joint byline. This does contain an aside stating, “it should be obvious by now that we don’t consider fantasy and science fiction to be irreconcilable aliens.”

I haven’t fully read the Winter-Spring 1950 issue yet but there does seem to be a considerable amount more science fiction in this issue than in the debut one. Perhaps of note, the editors have a tendency to refer to science fiction as “science fantasy” in their introductory paragraphs to stories even when, e.g., invoking the memory of a solid science fiction man like Stanley G. Weinbaum whose work really isn’t borderline.

Reactions to Selected Fiction

Time Quarry by Clifford D. Simak — Part II of III (Galaxy, Nov. 1950) — As I stated in my review of the first installment of this one, this is my first attempt at reading a serialized novel across multiple issues of a magazine. I think I actually like reading novels in these smaller snatches—it keeps me from getting slogged down in a narrative that is longer than it needs to be and the summary of the previous installment at the beginning was sufficient to refresh my memory.

I am interested in this one because it is vintage time opera. The big picture is compelling, a human empire stretched thin across the galaxy built on the backs of robot and androids slaves about to be ravaged by a changewar fought among: (1) the humans and androids who want the protagonist to write his book; (2) the humans who want the protagonist to write his book differently; and (3) the humans who want to kill the protagonist to prevent him from writing the book. The story also spends a lot of time in rural Wisconsin which is neat.

Still, I have beef. This installment gets all metaphysical. Our guy is writing a book about destiny which he has discovered is real and is guided by abstract conceptual symbiotic beings that live on a single planet in the galaxy and assign themselves to every lifeform that comes into being. Uhhh. Also both installments of this serial have ended with the protagonist getting hit in the head and rendered unconscious. Sloppy!

“Honeymoon In Hell” by Fredric Brown (Galaxy, Nov. 1950) — This one is Pat Frank’s Mr. Adam, D. F. Jones’ Colossus, and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ The Watchmen mashed up into a single story and accomplished in only thirty pages. My guess is that most of my readers haven’t heard of two of three of those works. Suffice to say this one is about supercomputers arranging a marriage and lunar honeymoon for an astronaut and a cosmonaut because male babies are no longer being born on Earth. That’s wild enough and it’s really just the tip of the iceberg. The computers have a secret agenda to end the Cold War by hypnotizing the newlyweds into believing they were kidnapped by aliens. A good one.

“Coming Attraction” by Fritz Leiber (Galaxy, Nov. 1950) — Post-World War III story where a British government official has come to America to trade British tech for American wheat. New York, still populated, is irradiated and you need special permission to go to New Jersey where it is less irradiated. American women no longer show their faces in public and instead wear masks that are supposed to titillate. The big pass time is watching masked wrestling, especially little guys getting wailed on by big women. The little guys all have a weaker woman back home to take their frustration out on after losing. The protagonist meets a woman and slowly realizes she is one such woman. She convinces him to take to her to England with him because she is afraid all the time. But she ends up standing by her abusive wrestler boyfriend when the British guy beats him up. Frustrated, the protagonist rips the mask from her face revealing pallid and plain features. Another good one.

“To Serve Man” by Damon Knight (Galaxy, Nov. 1950) — This one is a classic science fiction short story and was adapted into a Twilight Zone episode. I don’t relish taking contrary opinions but this story didn’t quite do it for me. I think its success or failure hinges on a surprise ending and, perhaps by way of cultural osmosis, I already knew what the surprise was. As an experiment, I’d like to invite anyone unfamiliar with it to read this story and see how you like it. Knight, at the very least, is a competent stylist. The story is short and goes down smooth.

“Private—Keep Out!” by Philip MacDonald (F&SF, Fall 1949) — Horror story where a man gets too close to finding out the meaning of the universe and is retroactively erased from existence along with his wife and child. The story is told from the perspective of a protagonist who has encountered a harrowed friend who is the last man that can remember the disappeared family. I am in ideological contention with this story because I believe the universe is ultimately more knowable than not. Moreover, to me, the idea that the universe has an intrinsic meaning is silly. These bones to pick did not hamper my enjoyment of the story which was well-executed.

“The Lost Room” by Fitz-James O’Brien (F&SF, Fall 1949; reprint from 1858) — For the contemporary reader’s sake, Boucher and McComas situate O’Brien as a contemporary of Edgar Allan Poe and bemoan his early death in the Civil War. They argue that if he had lived he might have been the founder of an “American un-Gothic” school of fantasy. This was an interesting introduction but after reading the actual story, I feel like I don’t understand what the Gothic is and why the story isn’t that.

The story is begins with the protagonist lying in bed smoking cigars in the sweltering heat and considering the origin of his various possessions in the dark. To cool off, he takes a walk in the garden of the boarding house he rents a room from. In the pitch black, he encounters a strange little someone or something who claims that the other residents of the boarding house are literal ghouls and that he knows this because he used to be one of them. When the protagonist goes back inside, he finds his room transformed and full of masked and lavishly dressed people laughing and having a feast. They try to get him to eat sumptuous meats—which surely must be human flesh—and become one of them but he keeps insisting they leave. Ultimately a masked woman agrees to gamble with him for the room. They play a dice game and she rolls a 13. He’s forced out of the room which proceeds to disappear. He is never able to relocate it or his various treasured possessions.

This story was very enjoyable. To my mind, it was the prose on the sentence and paragraph level that carried the story more so than the over all plot or concepts. I think it has held up. As an aside, this story showed some restraint in terms of its racism for a story first published in 1858 but it did feature a lazy Congolese manservant with filed teeth, so do with that what you’re going to.

“Rooum” by Oliver Onions (F&SF, Fall 1949) — I want to start by commenting on the elephant in the room. Oliver Onions is somehow a man’s real name. I really thought it was going to be a nom de plume. What a world.

This is the story I mentioned earlier that I said was arguably science fiction. I say arguably because the underlying premise of the story is basically scientific but is more-or-less underexplored along those lines. Instead, the affect is more suspense and horror.

The titular character is a construction worker. He is a highly skilled but wholly uneducated man who can fix things trained engineers can’t. He has the uncanny ability to detect water, e.g., 100 feet underground just by standing over it. He has a strange fear of echoes and, like me, is a free man who can’t keep a 9 to 5 schedule. The story comes in hot with a description of Rooum’s weirdness in racist terms. The narrator, an engineer with the proper certifications, says Rooum makes him think about Black people because he reminds him of Hoodoo.

Through many odd doings, it comes out that Rooum is being stalked by some kind of molecular opposite that is mingling with him via osmosis. In this process, Rooum is as a thicker liquid and the opposite is as a thinner liquid. As the thinner opposite gains more heft from Rooum’s thicker molecules—I’m butchering the science, I’m sure—the opposite strikes him down more and more forcefully. This tragically comes to a head at the end of the story.

The main thing going on though is a description of Rooum’s idiosyncrasies as he goes about his life and tries to seek out the book learning necessary to understand what is going on with him. I truly enjoyed this one and very much recommend it.

“In The Days of Our Fathers” by Winona McClintic (F&SF, Fall 1949) — Brief dystopian story about a precocious child in an emotionally regimented society that regulates and schools its members to prevent them from becoming “uncalm.” Our heroine discovers her black sheep pariah “unsane” uncle’s journal and starts to incorporate its contents into her mentality. She sort of gets caught and despite parental disapproval, she privately stays the course deciding that her uncle had the right attitude toward life. She plans to die laughing in a “unsane” home at age 78. This one was well-written, interesting and concise. Recommended.

“World of Arlesia” by Margaret St. Clair (F&SF, Winter-Spring 1950) — Another brief one, this time by a favorite author of mine (see review of “The Pillows”). It’s a second person narrative where a wife (the narrator) and husband (“you”) see a cutting edge immersive movie set in an exciting underwater world called Arlesia. “You” are immediately rapt but the narrator questions the verisimilitude of the experience and then discerns something sinister is going on. It turns out viewers of the movie never leave and believe they are turned into mermen and mermaids when really part of their brains are broadcast to the moon to work in the mines. For some reason, the process doesn’t take on the narrator and she is able to save “you,” though “you” are hapless and complain that the movie ended before you could be fully turned into a merman. This story is well-written. It is also an interesting example of an early VR story before there was a phrase for such a thing. On the VR front, see also “Pygmalion’s Spectacles” by Stanley G. Weinbaum.

“Not With a Bang” by Damon Knight (F&SF, Winter-Spring 1950) — Yet another brief one. I wanted to close on another Damon Knight story lest I be accused of being unfair to him in my review of “To Serve Man.” This one is a character-driven last man story where the protagonist is a cad trying convince the unbearably Protestant last woman to consider herself his wife so he can rely on her to inject him with antidotes to the plague and also so he can “use” and “beat” her without fear of her running away. Even as he seeks to charm and coax her, his internal monologue bemoans the fact that he doesn’t have the constitution to rape her and even fantasizes that she might bear him a daughter for unstated nefarious purposes. For her part, the last woman suspects the the protagonist is a bad man but believes that she can fix him. She is saved from her fate when the protagonist has an attack of the plague in a men’s room where she dare not go to administer the antidote because of her sense of propriety. I plan to read more Damon Knight. He was really onto something.