Covid Reading Diary 3: Selections from Galaxy October 1950

Isaac Asimov, Fritz Leiber, Katherine MacLean and Clifford D. Simak

Since this is a Covid reading diary, I’ll start with an update on my illness. All of my physical discomfort is gone now but I am still testing positive and I spent yesterday feeling listless and distracted. Indeed, I meant to have this post out yesterday but couldn’t bring myself to do much more than stare into my phone and eat small amounts of food.

Feeling much more focused now and I’m excited to share this one with you. Today I’ll be reviewing selections from Galaxy Science Fiction, October 1950, the first issue of that magazine. Its full contents has been scanned and uploaded to the Internet Archive, so you can follow along at home without having to shell out for your own copy of the issue.

As I’ve stated in the earlier installments of this Covid reading diary, I am only posting so much because I have time to read and write right now and will return to my normal posting schedule of one to two times a week when I am able to leave my house and resume business operations.

Nonfiction Content

As my readers know, I have a thing for magazines. I’m interested in how magazines cultivate an aesthetic and I’m interested in how the editorial function shapes fiction. For these reasons, I was hoping H. L. Gold would really lay it out for me in his introductory editorial. My expectations were too high!

The Editorial

There’s a little space devoted to reiterating what the title, “For Adults Only,” already communicates. This is going to be a magazine for mature readers. He doesn’t really say what this means. Then Gold proceeds to spend most of the editorial talking about the minutia behind the selection of the cover by David Stone, the cover stock and the engraving process. He hypes various things in the magazine, including a UFO-themed contest we’ll look at below, and closes with a call for critical letters.

The Back Cover

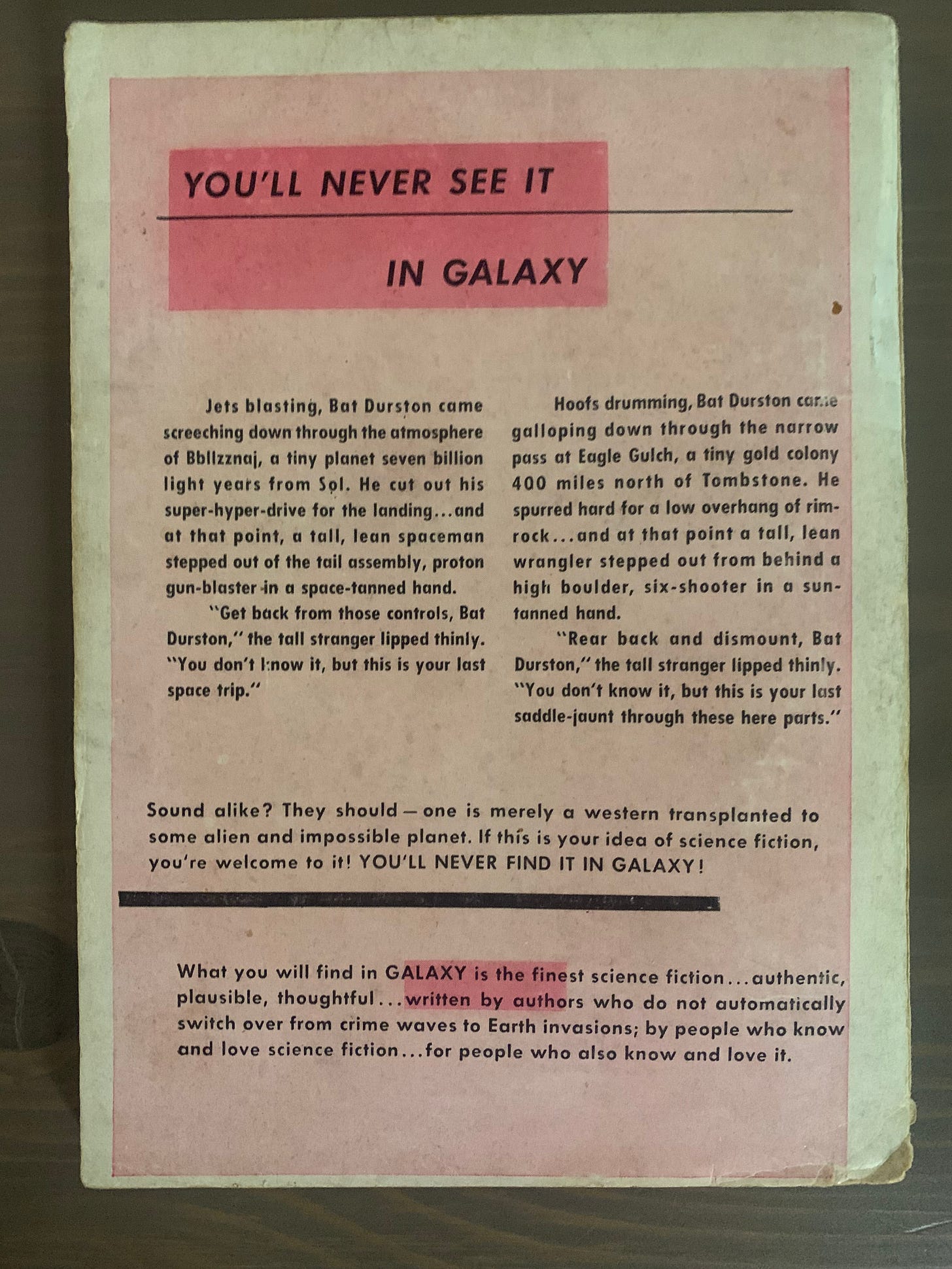

The back cover gives a better sense of what the magazine purports to be about if only by negative example. Peep it.

In 1950, the science fiction magazine market was experiencing a boom. Many were trying to enter the market and most lasted but a few issues or fell into obscurity despite sizable runs. Galaxy rose to the top of the field and is still well remembered by those who care to remember such things. I’m not aware of all the factors behind this. Here we see Galaxy trying to distinguish itself as a science fiction reader’s science fiction magazine by beating up on space Westerns.

From the vantage point of 2024, it’s not necessarily intuitive why science fiction aficionados of 1950 might have it in for space Westerns. Coming up the only proper Western I saw was Tombstone and I remain captivated by Val Kilmer’s performance as Doc Holiday. And I absolutely devoured the science fiction Western anime series Cowboy Bebop and Trigun, both of which are decent enough science fiction. I think I am a pretty serious science fiction fan and I have no beef with the genre mash up.

For a science fiction devotee in 1950 the situation was different. The output of Westerns in movies and fiction was torrential. They were ubiquitous. There were some gems among the movies of that era, 1952’s High Noon for example, but a lot of what was available were unmemorable action-heavy celebrations of masculine virtues. In fiction, Louis L’Amour was already ascendant in the dwindling pulp magazine and then new paperback markets with stories about canny and patriotic men carrying out Manifest Destiny. A person hungry for pure quill science fiction would likely begin to find the all-pervasive Westerns dull and repetitive by the time they were a teenager.

In this context, the back cover parodies stories that copy superficial space opera trappings onto oft regurgitated Western faire. In contrast, Galaxy promises “authentic” science fiction that is “thoughtful” (i.e., philosophical and idea-based) and putatively “plausible” written “by people who know and love science fiction” (i.e., this is a magazine targeted at fans). This last bit feels like a bold choice given what a rare animal the full blown fan of science fiction literature was and is. The fifties must have been quite a time.

“Flying Saucers: Friend, Foe or Fantasy?” by Willy Ley

Galaxy introduced itself to the world with a UFO-themed contest that belied its self-description as a serious magazine for grown ups. Readers were invited to write in a short explanation of what they believed was behind the UFO phenomenon. The best responses, as determined by agents of the Advertising Distributors of America, Inc., using openly unscientific criteria, would earn prizes. I’m interested to check out future issues and see what the people came back with but this veers toward Ray Palmer land and, insofar as a house ad for the contest suggests a Galaxy reader may actually resolve the UFO question in 200 words or less, insults the intelligence.

To give this all a scientific fig leaf, the contest details are preceded by a short article considering the UFO phenomenon written by a credible scientific authority, antifascist German emigres rocket scientist Willy Ley. As a science writer, Ley was a mainstay in the midcentury science fiction community and at Galaxy. It’s funny that his first appearance in Galaxy is in what we would now call ufology. To his credit, he fairly and economically considers various theories about the UFO sightings. His conclusions include that the UFOs are not Soviet aircraft or vehicles sent by civilizations on Venus or Mars. The only moment his scientific reasoning caused me to raise an eyebrow is where he says he would expect an interstellar spacecraft to be half-a-mile long but fails to explain why.

Galaxy’s Five-Star Shelf by Groff Conklin

This is the first installment of what would become the regular book review feature. At the time, Groff Conklin was a leading anthologist in the field. What’s funny about this column is that Conklin gives one of his own anthologies a positive review and contrasts it to one by August Derleth which he damns with faint praise. He manages to do this without the inherent absurdity of the exercise becoming too apparent. He also reviews a couple of novels about nuclear war, one by Judith Merril and another by an author whose name I have now forgotten. Over all, the review column was none too memorable.

Philosophical Sketches by Isaac Asimov and Fritz Leiber

In this section, I’m looking at two short philosophical sketches: “Darwinian Pool Room” by Isaac Asimov and “Later Than You Think” by Fritz Leiber. I’ll start by saying I think the former is bad and the latter is good and it comes down to their emotional impact. The Asimov piece seemed pointless, though it likely had a wry sense of humor to it that was lost on me because of my disinterest. By contrast, Leiber managed to be affective despite an inherent corny quality to his story.

The philosophy under consideration by Asimov has to do with evolution and the purpose of the universe which seems to be either anthropocentric or not and/or ruled by God or not. Three men, who seem to have psi powers, create a pool room and engage in a philosophical conversation about whether upon finding a pool table with all the balls in the pockets it is more likely that the set up was always that way or that a game of pool has been played. One man argues that Occam’s Razor points to the pool table always having been that way. Later the men talk about the purpose of the dinosaurs in human evolution. Perhaps they were a necessary prerequisite for human evolution and their destruction was not a cosmic waste. Further, maybe humanity’s own purpose is as a prerequisite for some higher former of life like AI. At another point, the factuality of the Big Bang is questioned. I can’t reproduce the arguments beyond this and am uninterested in revisiting them to try to. I basically don’t understand the stakes of this story.

Leiber too presents a philosophical conversation in the form of a short story. Unlike Asimov’s, his contribution is suspenseful, contains interesting descriptive details, involves characters one can actually differentiate from each other and deals with philosophical questions whose stakes feel evergreen. The story is about the meaning of intelligent life and how to look at the accomplishments of a civilization especially in light of the fact that all things end eventually. An astronaut has just returned from a long deep space mission where he was unsuccessfully searching for intelligent life. He has rushed to his archaeologist friend’s laboratory because the archaeologist was recently involved in discovering an extinct intelligent species on Earth.

The astronaut talks about the drive to find other intelligent life and his desire not to be alone in the universe. The interlocutors discuss the foibles and neuroses of the dead race including living in the psychological shadow of some kind of even older progenitor race they believed to have been greater than themselves. The astronaut and archaeologist muse about whether these progenitors were the gods the dead race believed in.

Over all, the astronaut finds the conversation disappointing and morose. What was the point of a civilization’s accomplishments if it died? The archaeologist philosophizes that they achieved what they achieved and that the present is always more important than the future. A species can’t claim all futures for itself. Some have to be left to others. This was likely poignant in 1950 with nuclear weapons on people’s minds. And I’ll add those weapons are still there and are just as destructive now if not more so. I can’t say I totally agree with the present’s eternal primacy over the future but there’s something there.

I wanted to engage with the philosophical content before getting to the trick Leiber plays at the end of the story. Throughout the story we get subtle and then less subtle clues that the astronaut and the archaeologist are not human beings. Eventually the archaeologist reveals to the astronaut’s great interest that the dead race were mammals. Humanity, one might ask? No, Leiber does this instead: the archaeologist explains that the extinct species had many languages but they all shared the same word for the name of the species itself. He can’t pronounce it, he says, because he doesn’t have the right vocal apparatus but he invites the astronaut to look at it transliterated into their alphabet. The name is RAT.

Frankly, Leiber was playing with fire here and a lesser author could’ve wrecked the whole story by doing this. If the story had ended at the philosophizing it may have been too grave and inert but it would have been interesting enough to read. Adding the subtle reveals throughout that the interlocutors weren’t human likely dealt with the potential inertness problem well enough. As executed, the rat reveal successfully added levity that punched the story up. But the trick ending is inherently corny and dangerous. What if it hadn’t landed? Well played.

“Contagion” by Katherine MacLean

This novelet is a medical drama about xenobiology and infectious disease. I like medical dramas because they are suspenseful. Also the theme of the professional overworking themselves for the benefit of others appeals to the residual Protestant and attorney in me.

The science in this story starts off believable enough—in colonizing other planets doctors, vaccinations and decontamination equipment all play important roles because of humans’ vulnerability to alien diseases—and goes to a truly wild, implausible place—designer human cells jump from man to man causing a fatal “melting sickness” but when regeneration vats used in cancer treatments are deployed the men’s bodies are totally restructured so that they can digest the nutrients of the alien planet on which the story is set and, incidentally, all the men get identical Greek god-like physiques.

The protagonist is a doctor named June Walton. She is accompanying three other doctors, including her fiancée Max Stark, on a hunting expedition from a recently landed spacecraft to determine if there are any organisms etc. in the blood of the local fauna that could be dangerous to humans. June’s party unexpectedly meets a beautiful, muscular man in a loincloth named Pat Meade who, naturally, belongs to a lost colony that mostly succumbed to disease some generations back.

Physical appearance is really important to this story. We learn pretty quickly that June is attractive. Her fiancée less so. June decides that Pat looks like Tarzan. June basically has the hots for Pat but feels guilty and reflects that she had never previously questioned her relationship with Max and wanted a future with him so much that she chose to travel through interstellar space with him.

Everyone on the ship is excited to meet Pat at first but he ends up being pretty disruptive to all the couples on board because the women all get interested in him and it makes the men sour. It turns out Pat sucks. When no one else can hear, he tells June that he wants her and then walks away. An order of magnitude or two worse than that, June uncovers that he has been knowingly infecting all the men with the aforementioned designer cells.

The men all get the melting sickness and are going to die until Max discerns that the disease works a lot like leukemia and they get out the cancer vats. Before he gets in the vat Max kind of figures out the whole score on everything and Pat laughs at him and says that he has an infectious personality.

When the men emerge from the vats they’ve all been transformed to look exactly like Pat but they are still themselves. Max asks June if she still loves him. She says of course but feels weird and privately wishes he were in his old body.

Outside a bunch of other Pats show up along with a young woman version called Patricia who the women now understand has come to do the same thing to them that has been done to the men. June’s clear view of the situation is that the men can’t leave the planet because they can now only eat nutrients from it and that the women can’t stay because they can’t eat its nutrients. Something has to give. The women are all upset and don’t want new bodies. Against their will, June lets Patricia into the ship to infect all the women.

There’s something weird about this one and I want to say it has some kind of deeper meaning but I’m not sure that it does. Relatedly, the planet is called Minos, like out of Greek myth, and I haven’t been able to come up with any kind of connection there.

As a science fiction medical drama “Contagion” does not go as hard as Lester del Rey’s 1942 novella Nerves but Nerves is too long and has science in it that is much more objectively provably wrong by comparison. My recommendation for science fiction heads who like shows like ER is to read both.

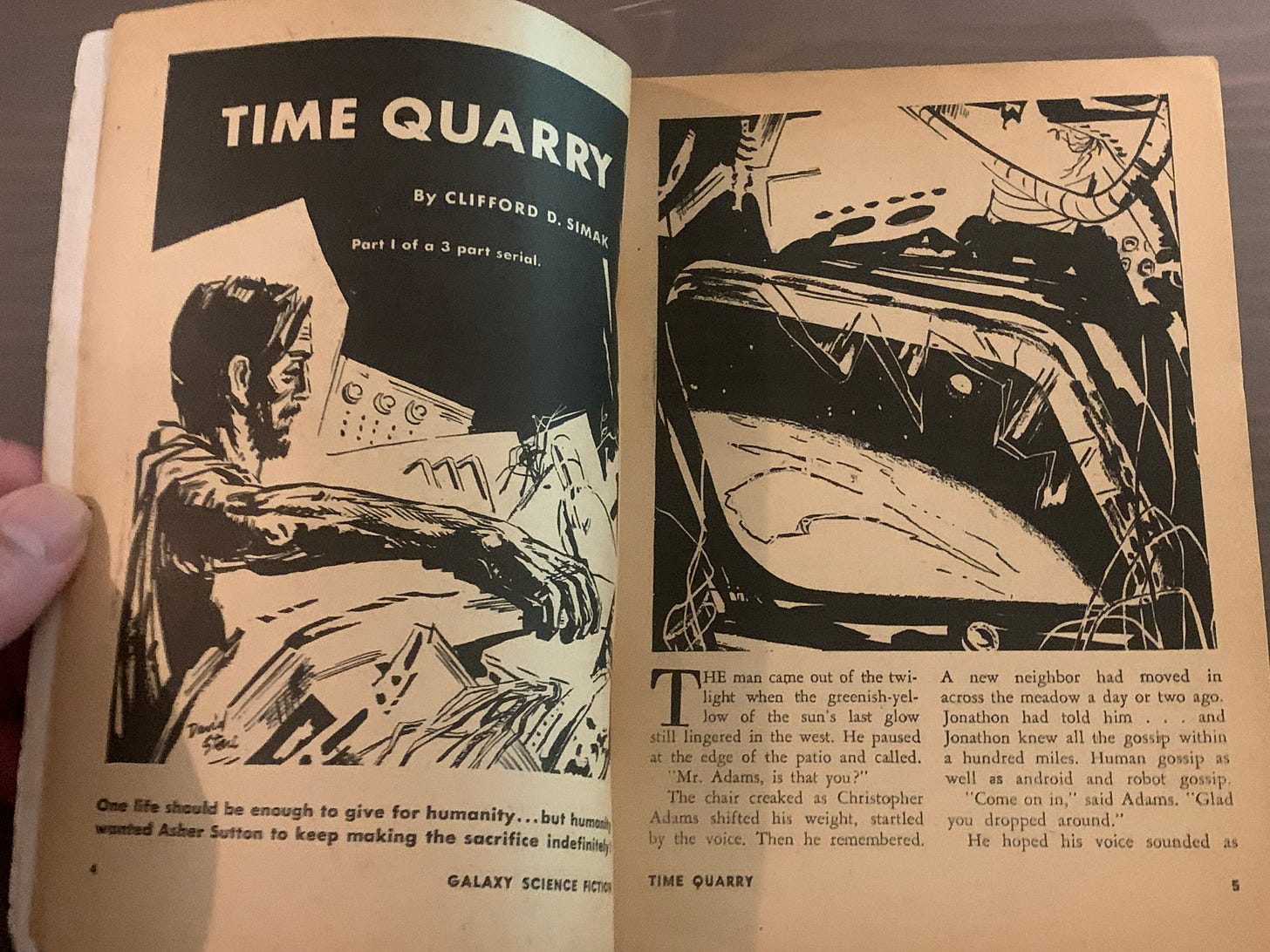

Time Quarry by Clifford D. Simak (Part I of III)

Serials! The bane and joy of the magazine reader and collector. Or so I hear. Truthfully most of the novels I’ve read out of a magazine have been in Planet Stories which didn’t run them as serials and Time Quarry is the first serialized novel I’ve actually managed to collect all the pieces of for the purpose of reading them as they were originally published.

This serial installment is doing three things for me. One, it’s giving me the experience of reading only one-third of a novel at a time like someone would have in 1950. Two, by being an interesting but incomplete story that ends on a cliffhanger it has seemingly locked me down to read the next two issues of Galaxy. And three, it helps me work on my longer term goal of reading more Clifford D. Simak. I’ve been picking quite randomly at different pieces of his body of work for three or four years now and I’ve never felt unrewarded.

The serial under review has a lot going on it in terms of science fiction ideas. The plot wasn’t hard to follow but was complex enough to be interesting and cuts off at a point where there is some mystery to it.

Man—and Simak always uses the masculine quasi-universal term here—has spread himself and his android and robot slaves out thinly across a galactic empire. Men do not die of accidents nor generally from the violence of androids, robots or aliens. However, men under 100 may not turn down a challenge to a duel and are allowed to kill each other.

There are two perspective characters. They are Christopher Adams, a high level supervising galactic intelligence agent, and the protagonist Asher Sutton, an agent who Adams sent out on a mission to 61 Cygni some 20 years ago and who returns to Earth near the top of the novel.

The novel opens with Adams being confronted by a man who claims to be his successor from the future. The man warns him that Sutton is about to return and exhorts him to have Sutton killed.

When Sutton returns there are many aspects that are strange. One, no one expected him back after 20 years except for Adams. Two, he was gone to a nearby section of the galaxy into which Man has never been able to travel. Three, he returned in a ship that was smashed in such a way that he ought to have been dead from the impact. Four, the windows of the ship were broken and it was not vacuum sealed in other ways. Five, he otherwise did not have an oxygen supply nor food nor water for the 11 light year journey home. Six, the ship’s engine was broken and would need a total rebuild to function. Seven, under examination by Adams’ team it becomes clear that Sutton’s body has been totally rebuilt in alien ways. Eight, unbeknownst to everyone but himself, Sutton is inhabited by Cygnian symbiotic entity of sorts he calls Johnny.

There are equal parts intrigue and pastoral sweetness. Sutton is taken by a woman named Eva Armour to an amusement place where they make your dreams real. He dreams of being a 10 year old fishing and seems to see her as an 8 year old before he is pulled out of it by a rich man who has challenged him to a duel and who has been mentally conditioned by parties unknown to kill him. The man shoots and misses and Sutton kills him. Mysteriously the fatal wound, Sutton learns later, is to the arm.

There is an interlude where an android attorney informs him that a robot who has been with his family for 4000 years and who was like a father to him after his parents died has run away to stake a claim on a planet far off somewhere in the galaxy. The robot has left him a chest full of junk. In the junk he finds an ancient unopened letter from the 1980s addressed to an ancestor who lived in Wisconsin. He pockets the letter and the thread is left unpulled.

Initially Adams will not take his time traveling successor’s advice to kill Sutton but then decides to flip on Sutton when Sutton refuses to tell him very much about 61 Cygni and when his agents find the title page of a book Sutton will write in the future in a perplexing burnt out car crash. Sutton himself finds a full copy of his future book in the pocket of a dying man when some kind of time ship crashes near him.

Soon after this Sutton is confronted by Herkimer, an android slave he has inherited from the man he killed in the duel. In order to get Sutton away from Adams’ agents to safety, Herkimer knocks him out for the purposes of carrying him off to a spaceship piloted by Eva Armour. The serial installment ends there.

For the purposes of a review, it’s hard to form an opinion about whether a plot works or not when you only see the first third of it. I will say I enjoyed this one and found the world eerie and engaging. There were lots of little interesting details that didn’t come out in this review that one could spend a lot of space cataloging. That there are only a small number of significant characters belies that the novel seems to be about events taking place in a time travel war across interstellar space and this juxtaposition contributes to the cultivated vibe of Man’s smallness in a vast universe. I hope this one doesn’t lose steam in coming installments.

Okay that’s more than enough for now. Perhaps I’ll be back tomorrow.