Return of the Reading Diary and On Collecting

Chan Davis, Marxism and Lysenkoism. Anthony Boucher. 1940s and 50s Digest Magazines. And a Pop-Up Event Saturday.

Greetings and salutations! Welcome to another installment of the Official William Emmons Books Newsletter. In this issue, I’ll be reinstituting two of my favorite recurring segments, the Reading Diary and On Collecting, and cluing you in to a pop-up event here in Richmond I’ll be selling books at this Saturday. I haven’t been pushing out much product online this week so sales won’t be a major focus. But, as always, I’d appreciate it if you’d peep my eBay and/or consider letting me curate a bundle for you.

Reading Diary

After some recent struggles with it, I am back into reading again. I still have my nose in Terry Bisson’s Voyage to the Red Planet and on Monday I started the Edgar Rice Burroughs Authorized Library audiobook of Tarzan the Invincible narrated by Ben Dooley. The former is for book club and the latter is for an article on Tarzan and Socialism for FarmerFan that should be debuting around PulpFest.* You can read my indignant tweets about Tarzan the Invincible in real time here. In addition to these novels, I snuck in the two novelettes discussed below.

*The fanzine article I was doing preliminary work on about labor in C. M. Kornbluth and Frederick Pohl’s novels didn’t come together due to time constraints but I should probably put up at least a mini-review of The Syndic at some point.

“The Aristocrat” by Chan Davis

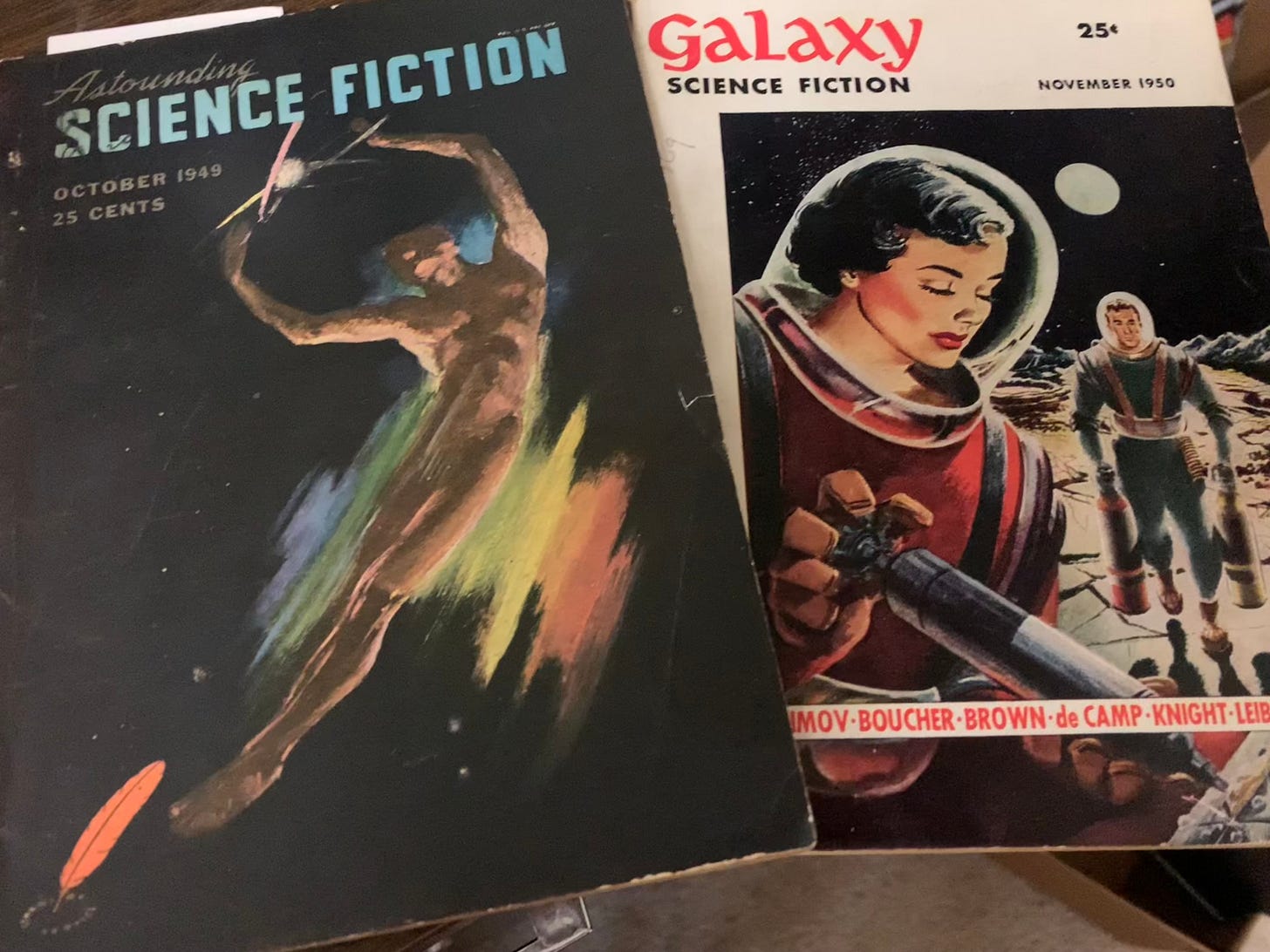

I recently acquired a copy of Astounding Science Fiction, October 1949, for, um, reasons and this turned out to be the lead novelette therein. It was a rich and edifying read by an author I’ve reviewed in this newsletter before.

One reason “The Aristocrat” is interesting is because it is simultaneously a post-apocalyptic political and sociological story and a hard sciences story about genetics. Narratively, Davis makes the unorthodox choice of telling the story from the perspective of a protagonist who is arguably the villain.

This narrator is a ‘normal’ human called Elder Stevan, an infirm 35 year old whose decrepitude is caused by lingering radiation from the final Atomic war. He rules over a village of illiterate, radiation-resistant mutant peasants called the Folk. Stevan considers the Folk subhuman and naturally unintelligent. But are they?

When Stevan’s ancestors, the first Elders, encountered the Folk after the war, the first generation of Folk’s human parents had died radiation-related deaths when the Folk were children and had only managed to pass on information about how to gather and open ration containers from bomb shelters. The Elders used the knowledge they gained from books to organize this ignorant population into a farming village and set themselves as quasi-theocratic despots who do no work and devote themselves to study.

Stevan is the last Elder, his parents having died before the story opens and his sister having not survived to adulthood. The story kicks off when a group of disobedient Folk villagers led by a man named Old Red go out hunting without Stevan’s permission and return having encountered a band of wild Folk hunter-gatherers from whom they have captured an anomalous ‘normal’ human called Barbi.

Though she is but 18 years old and speaks only broken English, Stevan immediately installs her as an Elder in his Temple and takes her to wife. He senses in her a native intelligence and he begins schooling her in literacy which she takes to quickly.

Notably Barbi is the biological daughter of the wild Folk’s chieftain. Before long she gives Stevan a baby. The catch? Her child is Folk rather than the ‘pure’ human child he had hoped for. Meanwhile down in the village the daughter-in-law of Jim Jenkins, a villager loyal to Stevan to the point of acting as a de facto secret policeman, has had the kind of ‘normal’ baby that Stevan craves.

Jim Jenkins reveals that unbeknownst to the Elders, the Folk sporadically have ‘normal’ babies but usually commit infanticide when they have them because the Folk fear the Elders will disapprove and most such babies don’t live long anyway. Stevan covetously moves Jenkins’ daughter-in-law and her baby to the Temple with the surreptitious plan of switching the children. For her part, Barbi is happy for the company but opines that she sees no inherent difference between the children.

Throughout the story, Barbi sits in on Stevan’s many dealings with Jim Jenkins and other Folk. Though at first she is silently observant, eventually she begins to question the society the Elders have set up. She refers to the Folk as Stevan’s slaves and, having voraciously read on all subjects including world history, points out that previous ruling classes have justified their position by claims of superior intelligence. Though the Folk have been kept ignorant, Barbi notes that whether they are necessarily so is untested because the Elders have hoarded the knowledge to their own benefit.

Stevan rebuffs Barbi’s criticisms with arguments that the actions he and his family have taken are only to rebuild civilization. Barbi’s rejoinder to this stuck with me. She says,

Look. You know what a civilized world is like, you want to see one built. Well, if it’s done it’ll be done by the people. You can’t just decide what it’d be nice to have happen. The men who are going to do it have to want to do it.

This is Davis’ post-apocalyptic science fiction answer to Bertolt Brecht’s “A Worker Reads History.”

As jarring as they might be, these conversations only happen a few times and don’t cause Stevan to question his position or Barbi’s loyalty. Instead he is preoccupied with the growing restiveness of the faction around Old Red and the genetic puzzle poised by the birth of the two children.

The main reason for growing discontent in the village is that Old Red and others want to spend more time hunting and foraging and less time farming. In order to keep Old Red’s people in line, Barbi proposes to permit them a hunting expedition led by her. Once his concerns about bringing the infant along are assuaged, Stevan enthusiastically consents to this plan.

I am having a hard time reproducing the various attempts Stevan makes at solving the genetic puzzle of the two infants which is embarrassing. It really doesn’t get more complicated than high school level Mendelian genetics and the question of dominant and recessive genes. In his basically racist desire for a ‘pure’ humanity to reassert itself and one day replace the Folk, he keeps coming up with wrong answers that make ‘normal’ genetic types a more likely outcome than they actually are. Eventually Barbi solves the problem as to how often ‘normal’ humans are likely to appear—it isn’t often but they will always be present—but the implications cause Stevan to despair because none of them would be ‘pure’ on the genetic level.

Stevan doesn’t have too long to despair. Barbi does not return from the hunting expedition in the fashion Stevan expected. Too late, he realizes the hunting expedition was a war council between Barbi, her father the chieftain and Old Red’s faction. A pitch battle ensues between that coalition and a smaller force loyal to Stevan which has barricaded itself in the Temple. Stevan fears for his life and the future of civilization as embodied in his books as fire arrows rain down on the Temple roof. He passes out.

He awakens a prisoner, surprised to find himself alive and the Temple library undamaged. Barbi explains the reasons for her actions. She too wants to see civilization rise again, but in her view the Elders’ set up actually made that less likely. By hoarding the knowledge, they created a situation that put it in danger of dying out. Further, she states that by leading the barbarian hunter-gatherers in she got out in front of an inevitable danger they posed to the project of renewing civilization. Thanks to her, the hunter-gatherers were able to see the beneficial golden eggs they could take from the village and were therefore unlikely to kill off the goose outright.

Barbi’s new dispensation turns the old arrangement on its head. Where before the Folk served and deferred to the most knowledgeable member of the community, under the new order, as in Ancient Rome, teachers, such as the ingloriously deposed Stevan, will be slaves. She says that scholarship is useful work and that people will always be interested in it but the new social stigma will prevent a restoration of the old order or something like it. In short, the former ruler and those like him who come after will be oppressed in order to force them to be useful to the community and keep them irrelevant politically. The term of art for this in Davis’ political tradition is dictatorship of the proletariat.

Indeed, in many ways, this is a text informed by the anti-racist, class conscious politics and philosophy of the Communist Party of the United States of America of which Davis was an on-again, off-again member until the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Davis portrays a class-riven society with a decadent ruler preoccupied with quasi-scientific ideas of racial purity. An outsider, armed with the weapons of literacy and theory, repudiates his views on race and fuses an emergent political faction led by a man literally called Red and her father’s (presumably communistic) hunter-gatherer band into a single party for the purposes of revolutionizing society so that the benefits of civilization are both preserved and more widely distributed.

In this sense, “The Aristocrat” is atypical of the era’s science fiction. The learned protagonist is brought low by an uneducated rabble led by an autodidactic barbarian woman. The cult of the competent, scientific man present in a lot of science fiction is besieged—literally in the course of the story’s narrative and figuratively by questions of whom and what knowledge should serve.

In another sense, the story is typical and a good fit for Astounding despite its editor John W. Campbell’s penchant for what we might magnanimously call conservatism. The protagonist is a man trying to solve a scientific problem. The genetic mystery made for good reading even if it didn’t quite stick to my ribs. I suspect that part of the story would have been an even better read to Astounding’s base readership of boys who aspired to be scientists and young engineers etc.

Interestingly, what makes “The Aristocrat” work in Astounding would likely have prevented it from being making it into a contemporary Communist publication. In writing a story based in part on Mendelian genetics, Davis implicitly challenged what was then Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. The story does not adhere to Soviet scientist Trofim Lysenko’s return to Lamarckian ideas about how traits are inherited. In essence, Lysenko rejected the idea that genes exist in favor of the idea that species develop traits through others means including exposure to different temperatures and inheriting traits acquired during a parent’s lifetime. Though Lysenkoism reached its apogee during the Stalin period, it remained the official line in much of the socialist world until the 1960s. Indeed, two months before this story’s publication, it became official Soviet policy that Lysenkoism was the only correct theory of inheritance and that criticisms thereof were necessarily bourgeois and fascist.

Perhaps a little spicy for a bookseller’s newsletter but I think the era of Lysenkoism shows that knowledge production ought to be (1) free to come to currently unaccepted conclusions and (2) be in the service of the community rather than any scholar or scientist’s individual career. Elder Stevan used science and knowledge to maintain political and economic power over his subjects. Lysenko used science, albeit bad science, to advance his career politically and suppress his scientific rivals. In a related vein, it’s also worth revisiting “The Engineer” by C. M. Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl on the consequences of a head engineer of a project viewing management and glad-handing as superior to his actual trade. Presently, scientists are forced to over-produce research in search of academic appointments and grants or work for private industry to produce shareholder value. I doubt Davis would actually see scholars and scientists as slaves but his story does beg the question how they might be better mobilized for the common good.

“Transfer Point” by Anthony Boucher

Reading this novelette marks the continuation of my journey into Galaxy Science Fiction. Last month, I read and reviewed the first issue dated October 1950. Now I’m working my way into the November 1950 issue.

“Transfer Point” is what the critics call a recursive science fiction story, i.e., a science fiction story “that refer[s] to science fiction. . .to authors, fans, collectors, conventions, etc.” It is also a time loop story, which isn’t an interesting idea in itself, though Boucher manages to work it well.

The protagonist Kirth Vyrko is the last man alive in a future where humanity has been killed off by a new inert gas that has entered the atmosphere. He is holed up in a retreat with the last woman alive Lavra whom he sort of hates and then comes to love and, in any event, with whom he conceives twins. He takes refuge in a collection of post-war science fiction pulp magazines, most notably the fictional title Surprising Stories in which he finds an author named Norbert Holt who accurately narrates future history and ultimately details of Vyrko’s own life in the retreat—leading up to Vyrko accidentally time traveling back to 1948.

Vyrko was a poet in his time and has no idea how future technology works so cannot trade on that. He also fears paradoxes from all his science fiction reading. So he raises some initial capital gambling on the Presidential election (“Dewey Defeats Truman” and all that), assumes the identity Norbert Holt and begins a career writing the science fiction stories he read in the pulp magazines.

He and the editor of Surprising Stories, a woman with the masculine name Manning Stern, fall for each other but maintain a solely professional relationship. He knows from the editorial preface to Holt’s last fragmentary story that he is going to die in a car accident. During their final encounter, Vyrko tells Stern that he wants to marry her but that he has Lavra and his twins waiting in the future. After giving Stern Holt’s last fragmentary story, Vyrko is promptly struck by a car.

Upon reading the fragment, Stern makes an unemotional decision fitting of someone with her surname. It’s not really a story and will only disappoint Holt fans. Moreover, publishing it will make her male colleagues question her judgment. She decides to run a proper obituary and pitches the fragment into the coals of a dying fire.

The next morning she has a vague impression of falling for Vyrko but no longer has a memory of him. Her adopted teenage daughter greets her in the kitchen and asks her who Norbert Holt is. She says she has the name in her head but she is not sure from where. Neither mother nor daughter remember Vyrko anymore.

The idea of a broken time loop shouldn’t be that interesting but Boucher’s artistry and poignant characters carry it. He’s got me living this crazy life where he, H. L. Gold and John W. Campbell (the big three science fiction editors of the 1950s) are all big literary interests of mine right now—a nice transition to On Collecting.

On Collecting: 1940s and 1950s Digest Magazines

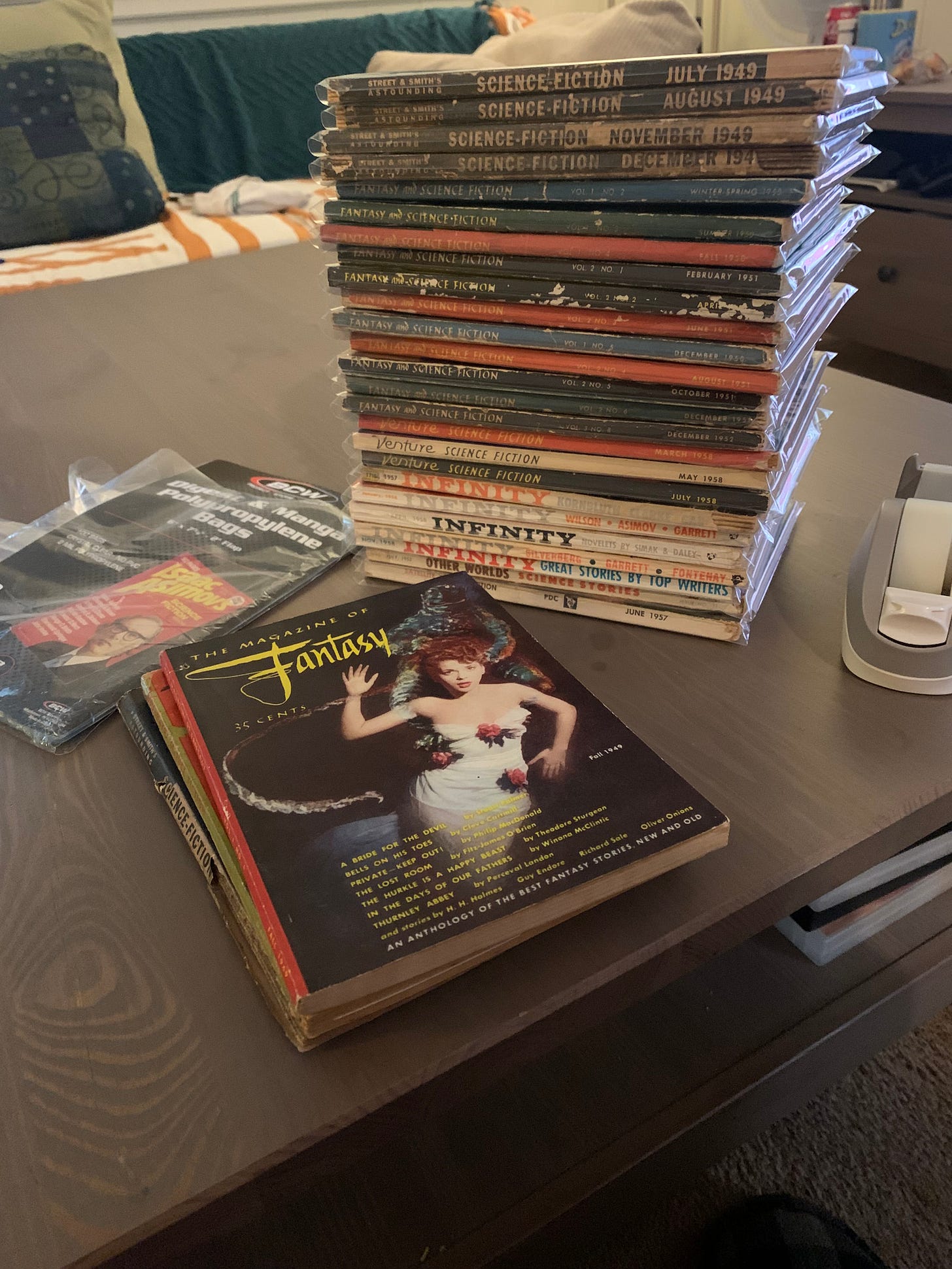

Why yes I did recently buy 28 magazines from the 1940s and 1950s. Thank you for asking. Real talk: I wanted to share because those of you who bought stuff from me last month helped pay for these as well as my electric and Internet bills and some groceries. For this I feel gratitude. If you would like to support my collecting science fiction and paying utility bills habits, I am asking you once again to check out my eBay or better yet consider letting me curate a bundle of vintage books and magazines for you.

Now, why did I buy these magazines? As longtime readers have intuited, I collect digest magazines because I like them and because I have an ambition to read them. I love short fiction and eventually I’ll get around to finishing one of these serialized novels—don’t think I’ve forgotten about Time Quarry. This is a little silly of me as most of the magazines I want to read are available as scans on The Internet Archive. But I have a fetish for the physical objects. What are you gonna do?

I’d like to go over the magazines I recently acquired and why I acquired them—

Astounding Science Fiction — 5 issues from 1949. This was the lead magazine in the field until The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Galaxy dropped in 1949 and 1950 respectively to give it a run for its money. I’ve read a handful of stories originally published in Astounding during John W. Campbell’s early years as editor in the late 30s and early 40s but my reading falls off sometime around 1946 when Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas’ Adventures in Time & Space anthology dropped. I was going to start collecting Astounding at 1950 to parallel my run of Galaxy but I noticed that the January 1950 issue has the third installment of an Asimov serial and that made me want to start at the tail end of 1949 to complete the serial which is frankly how they get ya. Haters stay mad at John W. Campbell—and for good reason—but they’ll never knock him down completely as evidenced by them staying mad and their inability to keep his name out of their mouths. Someday I’ll figure out why I like him so much and reduce it to words.

The Magazine of Fantasy/The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction — 12 issues 1949-1952. Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas’ SF/F magazine is credited for raising literary standards in the field. They also published fantasy which Astounding and Galaxy didn’t do. It’s wild to imagine Campbell and Boucher competing in the same field. The former was a left brained cretin compared to the latter who was Jorge Luis Borges’ first English translator. Anyway, I wanted these to complement my early issues of Astounding and Galaxy to see how they all compare.

Venture Science Fiction — 4 issues 1957-1958. Short-lived action and adventure companion to F&SF edited by Robert P. Mills who would go on to edit F&SF itself. The publisher had the notion that he could fill the hole in the market left by Planet Stories’ demise. I mainly picked these up because they had the same publisher as F&SF and these particular issues have a Leigh Brackett story and a C. M. Kornbluth story.

Unknown Worlds — 1 issue from 1953. I am putting together a particular serial from 1953 because one of the issues has a woman riding a large dog on the cover. This is a Raymond A. Palmer mag which actively repels me but I am interested in that Bea Mahaffey basically had to edit the magazine on his behalf for at least part of its run. Not sure where this issue falls in that timeline. She is credited as a co-editor.

Satellite Science Fiction & Infinity Science Fiction — 1 issue and 5 issues respectively from 1957-1958. Lumping these together because truthfully I don’t know much about them and bought them since they had authors I liked and were in a lot with some issues of Venture. My reading ambitions know no bounds so I want to take in not only the big three science fiction magazines of the 1950s but at least a small sampling from the also rans.

Pop-Up Event: Humane Society FUR-FEST Vendor Fair, Saturday June 8th 10AM-6PM

On Saturday, I’ll be slangin’ genre fiction books of all sorts at the annual Spring FUR-FEST Vendor Fair in support of the local Humane Society. My partner Meg will be there with me for at least part of the day and she has baked some homemade dog treats. It should be a good time. Come on out and see us!