Covid Reading Diary 4: Cordwainer Smith, Richard Matheson and more.

Plus the Question of Exposition Heavy Endings Considered.

I keep getting kind inquiries from friends, subscribers and business contacts about how my illness is going. I’m doing well. As of a few days ago, I was still testing positive for Covid but I am asymptomatic. I will test again Monday morning and see where I stand. I’d test more frequently but I have a limited supply of tests and they’re more expensive than I want them to be. Presuming I test negative, I will resume my regular schedule of posting only one to two times a week at the time.

When I started this week of reading and review, my goal was to look at fantasy as well as science fiction. I did manage to read and review one fantasy story along way but otherwise the content has been pure science fiction in part due to the fact that I read so much from Galaxy Science Fiction.

For this diary entry, I sought to rectify the imbalance by taking in a couple stories from The Best From Fantasy and Science Fiction Third Series and an issue of Beyond Fantasy Fiction. The effort was unsuccessful insofar as both stories proved to be science fiction. But those stories and others I’ve read over the past couple weeks have led me to consider the weakness of exposition heavy endings, including trick and surprise endings, in 1950s science fiction short stories. Before I start looking at stories that use this literary device, I have a brief reading note and a review of a Cordwainer Smith short story that are unrelated to this question.

The reading note is that I’ve started C. M. Kornbluth’s 1953 novel The Syndic (free audiobook here). I plan on reading a lot of Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl this month for something I’m working on that is unrelated to my business or this newsletter. Though, in general, I consider it best practice to make a public searchable record of reading reflections, I will mention this reading only in passing so I don’t lose any potency better exhausted on my project. That said, if you want to chat about Kornbluth or Pohl please hit me up. I could use the input.

“The Burning of the Brain” by Cordwainer Smith

Convention requires me to start by mentioning this one, like the last story I reviewed by Smith, is one of his many stories set in his Instrumentality of Mankind shared universe. I sort of hate this convention. As a reader and science fiction fan, I question whether or not series and shared universes have an over all deleterious impact on the literature and the way we think about it. Science fiction books and stories should have something behind them beyond a base reply to the market’s beckoning for more of the same.

What drew me to this story—which was originally published in the October 1958 issue of If and which I read out of NEFSA’s thick complete collection of Smith’s short science fiction The Rediscovery of Man—is the unique, intense and uninhibited nature of Smith’s work rather than my ability to comfortably fit into the familiar. Indeed these Instrumentality of Mankind stories are poignant and impactful in part because Smith, a CIA psychological warfare expert and practitioner by trade, works to disorient the reader with invented vocabulary and under-explained outré backgrounds.

My suspicion is that fans’ tendency to gravitate towards explicatory timelines and editors’ tendency to reorder the works into a perceived chronology come from an impulse to diminish the estrangement experienced by the reader. My tentative position is that mistakes have been made in treating the works this way because the setting is supposed to be unfamiliar. Worse, treatments like the explicatory timelines focus on mere details rather than themes and philosophy. As such, I reject these searches for sure footing and am instead reading the series by order of publication. The stories do seem to build by accretion but my estrangement feels intact.

“The Burning of the Brain” is a short narrative about what constitutes one’s real self. The primary characters are Magno Taliano, great Go-Captain of the fine interstellar planoforming ship Wu-Feinstein, and his wife Dolores Oh, previously the most beautiful woman on any planet but now very old and ugly from pridefully refusing rejuvenation treatments. These people seem to be hundreds of years old and to have always been celebrities. During their courtship the people cheered and their wedding was a great occasion.

Dolores Oh rejected rejuvenation treatments because she wanted to be her true self, not her beauty. This sounds somehow noble if a little cringe but actually she is portrayed as insufferable and insecure. When Magno Taliano’s niece Dita from the Great South House comes aboard the Wu-Feinstein, Dolores Oh’s greeting is described as an attack. It’s stated that Dolores Oh is a hag and sucks vitality from her great husband who has a strong enough personality for both of them. Dolores Oh explains to Dita from the Great South House that with her beauty gone, she knows that Magno Taliano really loves her since their is nothing else to love. For his part, Magno Taliano is portrayed as nothing but tender and loving to Dolores Oh. He does not resent her. No one really gets it.

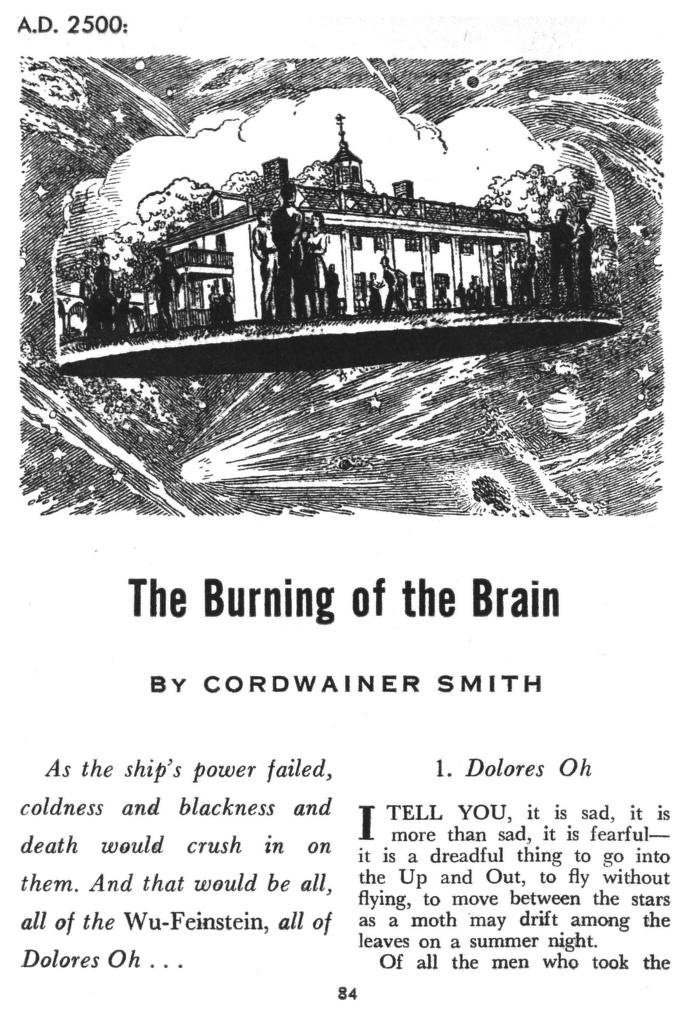

The plot of this story is that the Wu-Feinstein, which is a facsimile of George Washington’s estate at Mount Vernon by the way, becomes lost in deep space when the telepathic navigation equipment malfunctions and the maps Magno Taliano uses to will the ship through two dimensional space are irretrievably lost. The Go-Captain sends one of his pinlighters to collect his wife and niece so he can tell them about the grave situation. Dolores Oh makes the right motions but has long waited for such a catastrophe and is pleased. She says that at least she and her husband can die together and be together forever in that way.

The telepathic pinlighters see that deep in Magno Taliano’s paleocortex he is familiar with a star cluster that is visible from the ship. This means that he could bring the Wu-Feinstein home using his powerful telepathic brain alone. The hitch is that this will burn out his paleocortex. Not only will this be his last ride as a Go-Captain, it would leave him “intellectually sane” but “emotionally crazed” with no inhibitions with regard to “hostility, hunger, and sex.” He decides to do it for his niece’s sake.

By telepathically monitoring her uncle’s final flight, Dita from the Great South House somehow gains his profound psi powers. The final moment of the story is Dolores Oh happily leading her husband away. “He had the amiable smile of an idiot, and his face for the first time in more than a hundred years trembled with shy and silly love.”

The story raises the question of what constitutes a self. Was Dolores Oh really more herself by letting her beauty fade? We don’t get to know what her personality was like as beautiful younger person but as an older and ugly person, her insecurity and combativeness are unpleasant qualities. Maybe that’s what there is to her. What about Magno Taliano? With his emotional controls gone was he more or less himself? He seems genuinely happy to be with Dolores Oh in both instances. And then there’s Dita from the Great South House. Unlike her aunt and uncle, she gained rather than lost something. Did this make her more or less like herself?

A main theme seems to be sacrifice in the line of duty. This is an interesting theme to think about biographically. Smith was a hardened Cold Warrior who surely did and saw things one doesn’t come back from. In what ways had Smith burnt out his own brain by 1958? In Smith’s earlier story “The Game of Rat and Dragon,” pinlighters, telepathic space fighters that work in collaboration with cats, have very short careers because of the psychological damage that goes with the job. He thought about this stuff.

I thought this story was interesting and enjoyable. It distorts the trope that behind every great man is a great woman into something more unsavory and doesn’t seek to satisfy you with an ultimately unsatisfactory easy explanation of the couple’s dynamic.

Exposition Heavy Endings in Richard Matheson, James McConnell and William Lindsay Gresham

Recently I read and reviewed “The Last Martian” by Fredric Brown (review here) and “Later Than You Think” by Fritz Leiber (review here). The stories both rely on endings that are heavy on exposition. The former has a surprise ending where a fact is revealed that recontextualizes what came before in the story and the latter has a trick ending which is a surprise ending where the fact revealed is one the author has been actively trying to misdirect the reader from perhaps by telegraphing a different surprise ending. These are meant to be casual working definitions. Notably an exposition heavy ending need not be a surprise or a trick.

After reading “Third From the Sun” by Richard Matheson, under review below and which happens to have appeared alongside “The Last Martian” and “Later Than You Think” in Galaxy October 1950, I began to notice a pattern of endings heavy on exposition. The pattern became bigger when I read two more stories under review in this section, “All of You” by James McConnell and “The Star Gypsies” by William Lindsay Gresham. This isn’t a big or scientific enough sample size to make the conclusion that such endings were a common feature of 1950s science fiction. However, it is a reasonable sample size to conclude that it is not a device that enhances the quality of science fiction.

“Third From the Sun” by Richard Matheson

This story made me realize I’m developing sharper opinions about what makes for good science fiction. On a technical level there is nothing wrong with it. And it’s a fine psychological exploration of suburbanites smothered by fear of annihilation in the next war. It’s science fiction in the sense that it is about the pilot of an experimental government spaceship smuggling his family and neighbors off planet before the inevitable failure of their political leaders snuffs them out.

But the story doesn’t make for good science fiction. No science fiction ideas are really explored. It tries to make up for this with character work and then a dramatic surprise ending. The pilot explains to his wife that they are headed to an uninhabited planet that is contextually very obviously Earth. Perhaps universalizing Cold War fears into an inherent part of the human condition is a philosophical stand worthy of consideration but I don’t find it interesting or edifying.

“All of You” by James McConnell

This one first appeared in 1953 in the first issue of Galaxy’s short lived fantasy companion Beyond Fantasy Fiction. It’s a horny science fiction horror story about a lovelorn corpulent bourgeois man who has fled Earth after being tricked into marriage by a woman who wanted his money but who then sexually rejected him for being fat. He lands on the planet Frth where he is taken in and seduced by a young woman who is deeply attracted to how fat he is and who longs to make him even fatter.

The woman, who the man names Josephine, narrates the story which goes back and forth between her exhorting him to run for his life and flashbacks to their courtship which is interrupted by the matriarchal social customs on Frth. The Matriarch and her attendants take the man to the prison camp the eligible men are kept in and Josephine is chided to wait until mating season. Still she brings the man food at the camp.

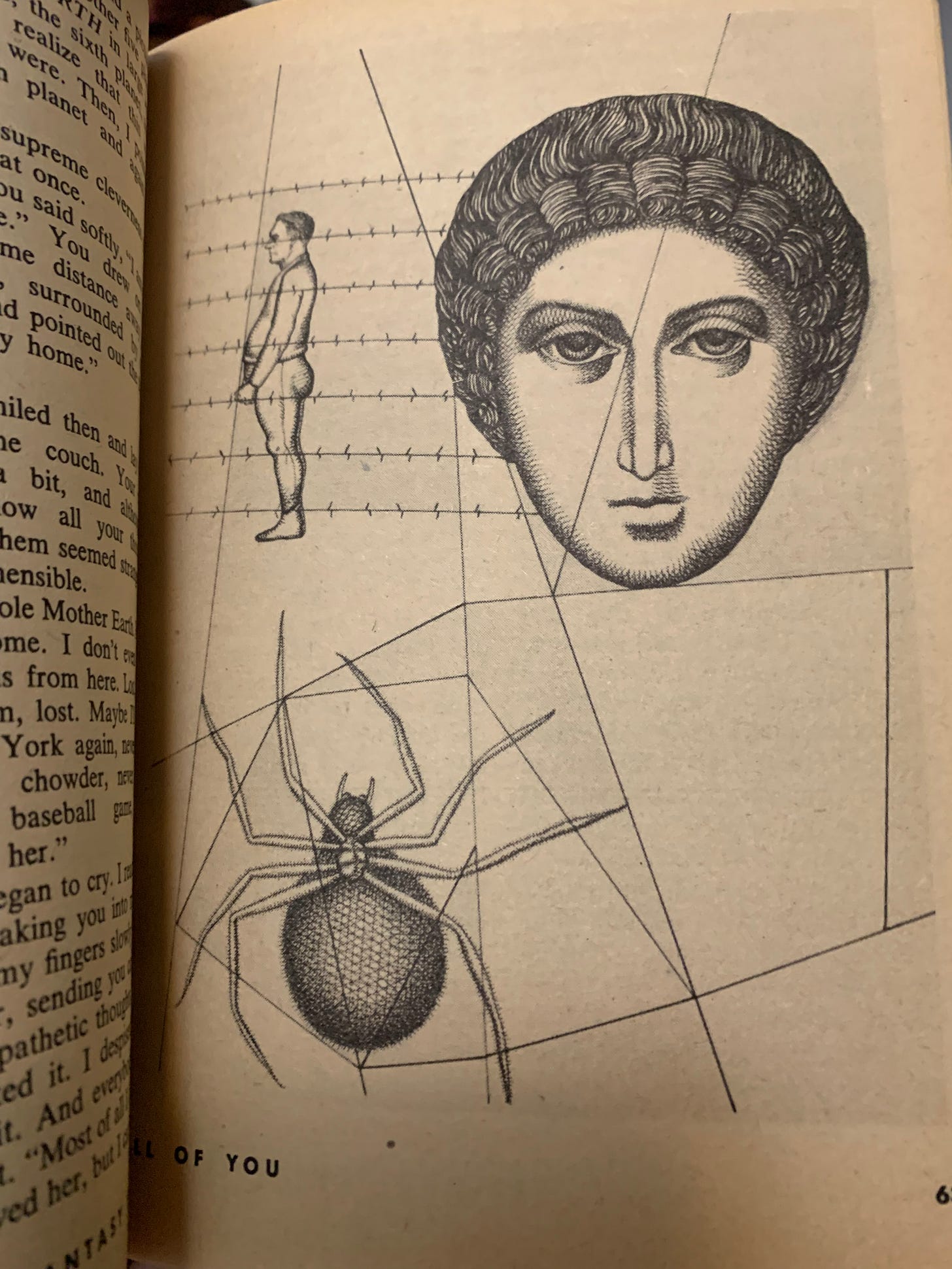

Social custom dictates that Josephine should have a fair chance at the man but her feeling is that the Matriarch is corrupt. Josephine narrates that since this is her first mating season she will have an opportunity to claim the man all for herself. The women seem to go into heat all at the same time, except sometimes first timers go into heat a full two days early. Here’s the surprise ending: going into heat means turning into a giant spider.

This reveal spends some time explaining the mechanics of how her toxins and egg laying work but the affect is more horror than science fiction. The reader gets to imagine the man paralyzed and placed in telepathic contact with the larvae who are slowly eating him.

Of the stories under review in this section, this one had the strongest execution of an exposition heavy ending and I think that’s because its purpose was to titillate more than to philosophize or convey an idea. I’m not trashing this story as science fiction, mind you. On the level of exogamy, the story is a horny reversal of Philip José Farmer’s The Lovers and therefore a worthy contribution to the field.

“The Star Gypsies” by William Lindsey Gresham

I’d been putting off reading this one, which first ran in the July 1953 issue of F&SF, because I feared the title implied that Romani were going to be used as some kind of metaphor for something else in a cringe way. It’s better than that in the sense the story actually is about Romani people in a post-apocalyptic setting and worse in the sense that it implies that Romani before the nuclear war were basically out of touch with modern society and felt culturally entitled to steal and in even in the post-apocalyptic context are unwilling to do the socially necessary labor to feed themselves.

Instead of working the Romani peddle in antique knowledge, teaching pre-modern technologies to the settled people, who live in a pitiful simulacrum of the old civilization, in exchange for gifts of food and cloth. This is the main science fiction idea in the story.

The plot is a love story about Fedar, a half-Romani prince named after FDR, leaving his adoptive father the king Johnny’s caravan to join a village because he has fallen for a non-Romani girl Thene. There’s a love triangle involving a young blacksmith named Klem whom Fedar fights and then following a tornado befriends and makes his blood brother.

The tornado destroys the village’s manually pulled combine and flattens all the wheat in the field. Knowing no way to harvest the wheat before it rots, all of the adults in the village succumb to a psychological disorder called the heartsickness. They return what of their houses the tornado didn’t destroy and passively await death to overtake them.

The youth have more pluck. Fedar and Klem work together to smith into shape some warped bicycles which they and Thene use to chase down Johnny’s caravan to get information about how to harvest wheat without a combine. Johnny shares with Klem the secret of sickles and adopts back Fedar along with his new wife Thene into the Romani caravan. Fedar, who once again will one day be king, declares a new dispensation that they will now share their secrets with the non-Romani freely.

The disjointed and unsuccessful exposition at the end is that the Romani were aliens all along and that they taught non-Romani people the use of fire and tools upon their advent on the planet. Non-Romani who escaped Earth before the nuclear war would have found more Romani in space. What’s more history has a long cyclical shape of non-Romani becoming too powerful and crushing the Romani before destroying themselves and then the Romani lording their secrets over the self-destructed non-Romani before the cycle begins anew. The prince Fedar’s new dispensation is merely another turn in the old cycle. These details feel rushed and tacked on and are therefore underexplored.

Gresham’s questionable project of portraying the usefulness of the seemingly uncanny pre-modern knowledge of the Romani in a post-apocalyptic context and conveying the idea of a cyclical shape to history driven by a dialectic between Romani and non-Romani would have been better served by telegraphing the latter idea sooner. The two ideas enhance and provide context for one another. The Romani as ancient astronauts idea might have been better left on the cutting room floor.

Conclusion

The use of exposition heavy endings, including surprise and trick endings, do not enhance science fiction as a literature of ideas. While they can be used to enhance the drama of a story, as in “All of You,” abruptly inserting ideas at the end of a story is not a good way to philosophize or consider concepts because ideas inserted in this way are not given room to breathe.