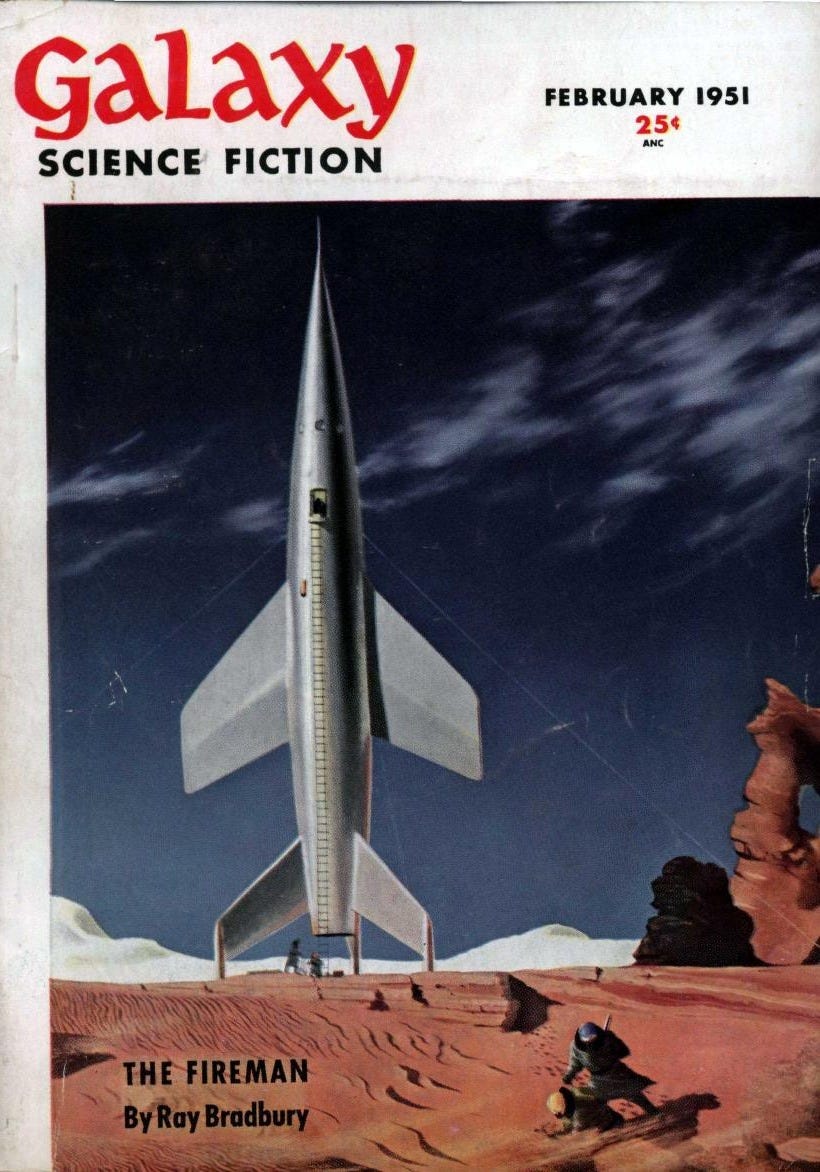

The last couple installments of William Emmons Books have been about medieval fantasy and sword and sorcery, so it’s good to get back into a classic science fiction magazine. The issue we’ll begin reviewing in this missive, the number of Galaxy Science Fiction dated February 1951, features that publication’s first real breakout hit in the form of Ray Bradbury’s novella The Fireman (later padded out into the famous novel Fahrenheit 451).

We’ll get into that novella in a later epistle. Today we’ll be looking at book reviews by Groff Conklin and the short story “The Protector” by Betsy Curtis.

In Which I Argue With 74 Year Old Book Reviews

There’s only five pages of nonfiction in this issue of Galaxy. Somehow I’ve managed to produce six paragraphs about these pages because book reviewer Groff Conklin touches one of my nerves as a science fiction reader who lately is also a fantasy reader.

Before getting into with Conklin, it’s worth mentioning H. L. Gold’s two page editorial. Though the editorial is mostly boosterism my heart sang a little bit when I got to the part where Gold busts off and says that he’s “mortally afraid of retread private eye, western and Congo Sam stories masquerading as science fiction.” I read fantasy and space opera sure but I am for pure quill science fiction that is the real deal.

But you can take your science fiction partisanship so far that it obscures your sense of what science fiction even is. This is one of Conklin’s sins. Previously I got rubbed the wrong way by Conklin’s review of a Robert E. Howard Conan book in the January 1951 issue in which he implies Conan is an intellectually inferior read to science fiction. I cannot emphasize how wrongheaded this is. I don’t claim to totally get Howard but he wrote with some heft.

In the issue under review, Conklin continues in this vein with shots fired at the collection A Gnome There Was by Lewis Padgett1 and at a reissue of the novel The Ship of Ishtar by A. Merritt. Of the former, he says it’s seminal stuff except the hillbilly exploitation Hogben stories (fair) and the two “out-and-out fantasies.” He at least vaguely describes these two stories and gives one-to-two word reasons for why he thinks they’re bad.

Conklin gives much shorter shrift to The Ship of Ishtar, a work of fantasy he claims to like if only for nostalgic reasons. He spends half a column of copy refusing to actually review the The Ship of Ishtar or tell the reader what it’s about. He explains that if one likes Merritt one likes Merritt and if one doesn’t, well, there’s no convincing someone who doesn’t like Merritt to like him. This maneuver is proceeded by a gesture where Conklin throws up his hands and proclaims the novel antiquated because it was first published 27 years prior to his review.

By contrast, Conklin gives around two and a half columns to Robert A. Heinlein’s then-new juvenile novel Farmer In The Sky. He praises the book for its “realism” and for not giving scientific descriptions of how Ganymede became habitable. Conklin doesn’t laud Heinlein for delivering science fiction so much as he lauds him for delivering an adventure in a strange place. Taking us back to Gold, this kind of adventure writing with science fiction window dressing raises the specter of “retread. . .stories masquerading as science fiction.” If Conklin could be won over by science fiction window dressing, adventure, and whatever he means by realism, it begs whether his problems with fantasy were more about ideology than discernment. What I mean by this is that perhaps Conklin held an ideological belief in science fiction’s superiority to fantasy without having articulated for himself core theories of how either genre works. In any event, reading these Conklin reviews is frustrating now that I’ve read roughly contemporaneous reviews from James Blish (“William Atheling, Jr.”) and Damon Knight who were much sharper and more astute.

“The Protector” by Betsy Curtis

This story is interesting because it is a self-conscious working through of the use of aliens as stand-ins for subjugated natives in colonial narratives. I don’t like where it ends up or how it gets there. It’s worth consideration nonetheless.

The underlying premise is that on an alien planet called Gorlin there are “primitive tribes” of humanoids called Anesthons. The principle trait of these Anesthons is that they don’t feel pain.

The narrator-protagonist of the story is an Earthling boxing manager. He has taken advantage of the Anesthons’ unique quality by bringing one of them, a man the narrator has dubbed “Pierre,” back to the Solar System and setting him up as a champion prize fighter. All is going well till one day Pierre comes across a news item that says his people are going extinct. The narrator tries to downplay the import of the news story but this doesn’t get him anywhere with Pierre.

Pierre hasn’t reached the pinnacle of his boxing potential yet but he has got himself and the protagonist set up pretty well. Such being the case, the narrator ultimately agrees that Pierre should take a break from fighting and return to Gorlin to try to help his people. To wit, the narrator decides to go with him in order to protect his investment. Pierre is always on the verge of unknowingly breaking his leg etc. Moreover, one gets the sense the narrator genuinely cares about Pierre—even if recruiting a “primitive” who doesn’t feel pain to come to civilization to fight people for money does seem like an asshole move.

When the pair arrive on Gorlin, they discover that the planet has been transformed by large scale capital investments in hospitality and mining. The real culprit in the die off is in mining. There are two problems. One is that the Anesthons are basically naive and willing to do hard labor in exchange for small luxuries. They are unsophisticated in the ways of heavy industry and are therefore prone to deadly accidents, a circumstance exacerbated by not feeling pain. The second problem is that the Earthling mining boss loathes the Anesthons, only cares if they die insofar as it inconveniences him, sets quotas too high, and has taken no occupational safety and health measures.

The structure of this story is not subtle. The narrator solves the problem of the mining boss quickly by encouraging Pierre to punch him in the face. The narrator then calls the colonial authorities on the mining boss who promptly remove him for his excesses. In turn, the colonial authorities resolve the problems poised by the Anesthons’ naïveté by appointing the narrator to be their official Protector.

This would be run of the mill stuff about a white savior and simple-minded natives but for the jarring addition that the natives don’t feel physical pain. An almost redeeming and sadly undercooked element of the story is that the Anesthons do feel a great deal of psychological pain. A would be worker who was rejected by the mining boss takes it so hard that he seems to be lingering in the jungle waiting to die. Pierre’s sister winces at the mere mention of the word “native.”

This last detail is particularly evocative. There is no such thing as a native except in relation to a colonial power. This relationship itself is painful even for a colonial subject characterized by her inability to feel pain. This recognition of the pain inherent in the colonizer-colonized relationship is obscured and undermined by the protagonist’s assumption of a role in the colonial machinery in which he acts in loco parentis to the whole Anesthon population.

In the story, this change in personnel changes the nature of the colonial relationship. The narrator in his new position finds himself constantly crowded by his adoring charges. In real life, you can’t dress up a relationship based on one party extracting a maximum of resources and labor from another in exchange for a paltry minimum of inputs in such a way that makes the relationship in actual fact good and noble. In real life, you can’t establish and maintain such a relationship without marshaling organized violence and a reality-distorting ideology.

Some Process Notes On Fiction Unreviewed

I realized that I already took in most of the short fiction in this issue of Galaxy last year as episodes of The Lost Sci-Fi Podcast. Of the stories so consumed, I have not bothered to reread “Two Weeks in August” by Frank M. Robinson (audiobook here). It’s a decent enough joke story about workplace jealousy and keeping up with the Joneses. I won’t be reviewing it because I don’t think it’s particularly thought provoking.

I did relisten to The Lost Sci-Fi Podcast episode of Lester del Rey’s story “. . .and it comes out here.” I won’t be giving this one a full review. It’s a time loop story whose use of the concept doesn’t capture my imagination. What I will say for the story is that it’s strong in terms of prose. Craft can’t carry a science fiction story though.

This issue of Galaxy also contains the second installment of Isaac Asimov’s serialized novel Tyrann. Unless the middle third of that novel proves to be a drastic improvement on the first third, I will leave it unreviewed as well.

Pen name shared by husband-wife duo Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore. Conklin attributes all of the stories in A Gnome There Was to Kuttner but I don’t believe that is accurate.

Thank you for this review. I reviewed Curtis' first three published short stories -- “Divine Right” (1950), “The Old Ones” (1950), and “The Protector” (1951) -- in my ongoing series covering early work by female authors I need to know more about. Like you, I can't say I was super impressed, unfortunately, with Curtis. I am interested in reading her Hugo-nominated short story “The Steiger Effect” (1968).

The substantive part of my assessment: "“The Protector” reads like a tentative condemnation of colonization that resorts to a simplistic violence solves everything message i.e. if only those who feel no physical pain inflict physical pain on others then the evil colonizer can be defeated. Of course, an external savior is needed to convince the natives to resist. There are deceptively powerful moments that lay bare the exploitive impact of external culture on the Anesthons: “I see one Anesthon girl — a real looker she is, too — dance fourteen hours before she gives out, just for a bottle of perfume and one of them Venusian fur lounge robes” (76).

Perhaps a scholar interested in 50s SF’s response to the first stages of post-WWII decolonization or lesser known female authors in the renaissance of the 50s might find Curtis’ tale of value for a larger historical argument. I’m glad I read it (immediately thinks of larger projects half formed). All other readers will be disappointed."

If I may, here's the link to the full review: https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2022/12/03/short-story-reviews-betsy-curtis-divine-right-1950-the-old-ones-1950-and-the-protector-1951/

I adore the Hogben stories because they changed my way of viewing the world. They were the first stories I’d ever encountered in which superpowers are the prerogative of the despised and downtrodden and not the intellectual elite. Given that Kuttner and Moore’s Baldie stories were the major source of Marvel’s X-Men, there’s something deeply significant there.

I’ve never read Farmer in the Sky, but I believe it’s the Heinlein novel in which there are microwave ovens but they’re only used to prepare a meal of steak and potatoes. Given that Heinlein first came to notice for stories which argued that changes in technology would inevitably bring about sweeping changes in society, he had a real blind spot when it came to using futuristic gadgets as window dressing but never considering their effect on the lives of people who used them.