Not so long ago, I wrote a little about the Robert E. Howard story “Wolfshead” and beat up on Howard for being racist. He definitely deserves such blows. Unfortunately, in writing about that aspect of his work I failed to make any real comment on its literary substance or elucidate what I actually like about it. Today I hope to begin to rectify that error.

Intuition tells me that contemporary fantasy readers under a certain age aren’t particularly aware of Howard.1 The historicist in me wants you to read Howard’s short stories because he’s the father of the American iteration of fantasy’s sword and sorcery subgenre. Moreover, even if you don’t care about canon, you should want to read Howard on his literary merits. Come for the swashbuckling and bloodletting and stay for the passions, the ruminations, and the weirdness.

Theses on Kull

In the following theses, I’ll be discussing Howard’s first recurring sword and sorcery character Kull with the goal of systematizing some of my own thoughts. To this end, some of the theses will be about sword and sorcery and Howard more generally.

On the Nature of Sword and Sorcery. I’m a novitiate in the ways of sword and sorcery but I share Albert Einstein’s opinion that lay people ought to comment on fields outside their areas of expertise. I believe that sword and sorcery in its purest form is about a canny individual using all of their wits and strength to struggle against a hostile universe. When I think about sword and sorcery, I am not thinking about J.R.R. Tolkien’s kind of epic fantasy even though the latter objectively involves both swords and sorcery. For me, there’s too much order in Tolkien’s universe. Others may have a more expansive definition of the subgenre. In the 2023 issue no. 366 of the revivified (undead?) magazine Weird Tales, editor Jonathan Maberry includes both Tolkien and N. K. Jemisin in his list of sword and sorcery practitioners. I scratch my head at this.2

On the Alienness of Robert E. Howard. I struggle with Howard because I don’t quite get him. I like to think I could’ve corresponded with his friend and Weird Tales colleague H. P. Lovecraft. I don’t feel that way about Howard. His idea that civilization and barbarism rise and fall in an eternal cycle is one I can understand. I also get reacting negatively to modernity. What I can’t quite get into is reacting to modernity by wanting to embrace barbarism. I also don’t understand what, to Howard, drives the barbarian.

On the Alienness of Kull. Because I don’t fully understand Howard, I don’t fully understand Kull. Kull is an eternal foreigner who was raised in the wild by tigers before being adopted by the barbarian tribesmen of Atlantis. Upon entering civilization, he became a galley slave and rose from that station to become king of the antediluvian empire of Valusia through his strength and wits. This I understand and find compelling. But why he wanted to be king is a mystery to me. As a barbarian, he hates ruling over civilized and decadent people with ways he doesn’t understand. Does being a barbarian drive one to seek the top spot despite its draw backs?

On the Obvious. Part of what sword and sorcery entails is what it says on the label. The subgenre involves pulse-pounding action and sanguinary doings. There are monsters, mayhem, and magic. Where I’m sort of a renegade as a budding sword and sorcery devotee is that action writing doesn’t do that much for me. I’m not offended by blood and guts and I do go in for writing about organized violence on a macro scale but sometimes the action feels repetitive and takes me out of the story.3 For example, there’s much I like about the story “The Cat and the Skull” but I found myself distracted during the parts of it where Kull is in a forbidden lake fighting various sea monsters.

On the Weird. What draws me to Kull is just how strange the things he experiences are. This is from the first Kull story “The Shadow Kingdom” forward. In that story, Kull is brought into the confidence of a cabal of Valusia’s barbarian Pictish allies. In this way, Kull becomes aware of a prehistoric conspiracy of snake men who can impersonate anyone and who are secretly pulling the strings of Valusian politics. In later stories, Kull comes upon things much stranger still. In “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune,” Kull is almost undone by contemplating mystic mirrors for too long. In “The Screaming Skull of Silence,” Kull seeks out an ancient castle where a primordial wizard-philosopher has imprisoned the Platonic essence of silence.

Reality According to Robert E. Howard. One thing to recommend Kull is that the stories are infused with heavy philosophical concepts conveyed by strange figures. In “The Cat and the Skull,” Kull is tricked into traveling to the bottom of a forbidden lake where dwells an ancient race of lake people. In order to be left alone and avoid war, these beings made a pact with a king of Valusia in a past millennium to make the lake taboo to surface dwellers. After clearing up some mutual misunderstanding and renewing the pact, Kull questions the lake-king whether the realm of the lake people is really at the bottom of the lake or if they are somewhere out to sea. The lake-king gives a most ontological answer:

You are at the center of the universe as you are always. Time, place and space are illusions, having no existence save in the mind of man which must set limits and bounds in order to understand. There is only the underlying reality, of which all appearances are but outward manifestations, just as the upper lake is fed by the waters of this real one.

Reality According to Robert E. Howard, Cont’d. In “The Striking of the Gong,” Kull has an out of body experience following a failed assassination attempt. He finds himself naked in another plane of existence talking to a murky, nondescript personage. Understandably Kull wants to know where he is. Instead of a straightforward answer to Kull’s question, his interlocutor provides more ontological discourse:

Worlds within worlds, universes within universes. Things exist too small and too large for human comprehension. Each pebble on the beaches of Valusia contains countless universes within itself, and itself as a whole is as much a part of the great plan of all universes, as is the sun you know. Your universe. . . may be a pebble on the shore of a mighty kingdom. . . .

You may be in a universe which goes to make up a gem on the robe you wore on Valusia’s throne or that universe you knew may be in the spider web which lies there on the grass near your feet. I tell you, size and space and time are relative and do not really exist.

How to Read Kull

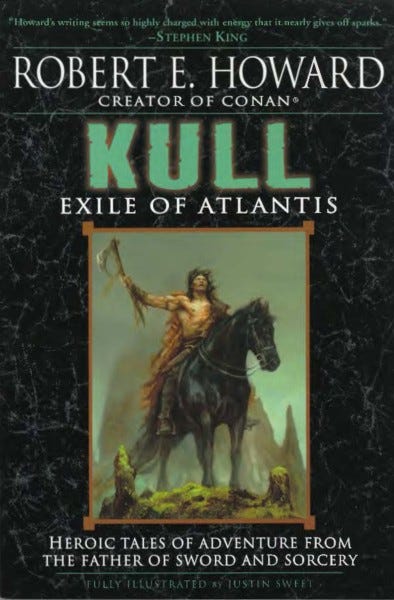

A pair of the stories mentioned herein were published in Weird Tales during Howard’s lifetime and I have provided links to the Internet Archive for those above. However, most of the Kull stories were published posthumously and are still under copyright. To get the full Kull experience, I recommend checking out the 2006 Del Rey Books volume Kull: Exile of Atlantis. It is available both as a trade paperback illustrated by Justin Sweet and as an audiobook narrated by Todd McLaren.

Even those readers ignorant of Howard likely have a passing familiarity with his most famous creation Conan the Cimmerian.

At least one expert agrees with me. In the recent issue no. 13 of the sword and sorcery magazine Tales From The Magician’s Skull, editor Anton Kromoff takes a crack at the question, “What Is Sword & Sorcery?” He writes:

Sword & Sorcery is a subgenre of fantasy that revolves around brutal combat, fast-paced action, strange supernatural elements, and heroic adventure. The stories typically follow characters who rely on their physical abilities and wits to navigate dangerous, unforgiving, and often bizarre worlds. Magic exists in these tales, but it’s wild, alien, and unpredictable. . . .In these stories, more often than not the stakes are personal, focusing on quests for wealth, revenge, or survival rather than world-saving missions[.]

For my taste in action writing, see, e.g., the battle scene in the Kull and Bran Mak Morn time travel crossover “Kings of the Night.”

I’ve developed an aversion to most fantasy and especially sword and sorcery, but I enjoyed reading your thoughts. I feel like the genre lends itself to lazy storytelling and worldbuilding with no internal consistency or coherence. Obviously there’s a lot of bad SF like that, too, but at least the genre in general aims towards coherence with scientific principles.

I find I have to be in a very specific mood to tolerate fantasy. Do you approach the genres differently?

Lately I’ve been a heavy reader of urban fantasy, while avoiding like the plague anything that has “epic” or “kingdom” in the description. For example, I just finished a novel whose protagonist is a magically endowed librarian in New York City struggling against proposed legislation that would essentially reduce all magic users to slaves of a dictatorial government. Now that I can relate to, while muscle bound swordsmen battling fish monsters leave me cold.