Here at William Emmons Books, I have been developing a hypothesis of proletarian science fiction. I have described it as a type or “vein” of science fiction where the protagonist is a worker rather than a middle strata scientist or space captain and which challenges science fiction’s bourgeois values and assumptions.1 As a hypothesis, proletarian science fiction is not yet fully fledged. One thing holding it back is that I have failed to articulate the purpose and stakes of the hypothesis.

Today I hope to start rectifying this problem by exploring the possibility that proletarian science fiction is less a “vein” in the literature itself and more a critical technique for interpreting it. The stakes for this flow from my understanding, following Hugo Gernsback, that science fiction is a means for explaining and changing the world. The Gernsbackian true believers thought that science fiction shapes history by encouraging people to become middle class scientists who midwife the future through science and technology.

By contrast, I believe that science fiction ought to have a broader appeal and purpose. While I enjoy speculation in the areas we usually talk about when we talk about “science” (hard, soft, whatever), I am personally more preoccupied with social relations. Within the current set of social relations, my general focus is on the status and agency of the majority of the population constituted by working class people.

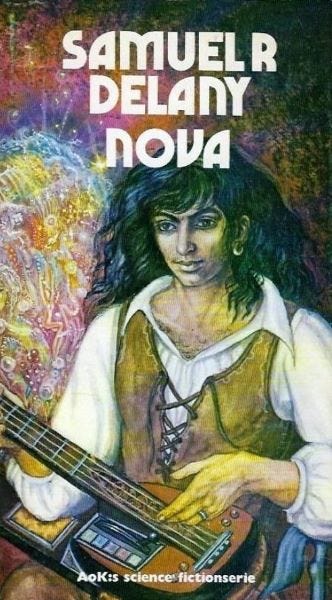

For this reason, I turned with interest to Samuel R. Delany’s 1968 novel Nova. As a piece of art it is sound with only a couple minor infelicities. As science fiction literature it is an achievement, successfully combining space adventure with speculation about astrophysics and the development of interstellar cyborg society.

That said, from the perspective of proletarian science fiction, it is a bait and switch. The book seems like it is going to be about the Mouse, an 18 year old Romani sailor and musician who had a lumpen childhood. In fact, it is mostly about Lorq Van Ray, a space captain and the scion of the Pleiades’ wealthiest family.

At the beginning, the reader is regaled with stories of how the Mouse stole a multi-sensory musical instrument called a syrynx from a bazaar in Istanbul, got a gold earring sailing the Indian Ocean, and became a cyborg relatively late in life as a teen in Australia. We learn that due to a neurological defect to his vocal cords, the Mouse speaks very coarsely. On Titan, the the Mouse is recruited along with a number of other cyborg proletarians from across the galaxy by Van Ray. The Mouse and his new crewmates are henceforth enthralled to Van Ray’s powerful will.

Van Ray is on a mission, or in the novel’s own metatextual formulation “a quest,” to fly his spaceship into a nova and collect several tons of Illyrion. Illyrion is a fictional element and power source which in large quantities will destabilize the galactic economy and shift the balance of power in favor of Van Ray’s family and the Pleiades. He’s challenged by rivals who are the heirs of a wealthy family from Earth. It’s space opera about a struggle between elites. The fate of the galaxy comes down to the actions of three individuals.

Still a theme of the novel is that the Mouse is an essential man of his times. Notably, even as this theme is explored, the Mouse is revealed and developed dialectically against Van Ray and especially against another shipmate named Katin Crawford.

Katin is a bohemian Harvard grad working in an antiquated art form called the novel. He is constantly adding to his copious notes on the novel though he does not know what it will be about. In discourses with the Mouse, he considers the potential subject of his novel. In one of these discourses, he directly declares that the Mouse is the true representative of the galactic cyborg culture.

Initially the Mouse can only speak roughly about his own status and relations to society and the universe. In this sense, his neurologically defective vocal cords are symbolic. He can mainly express himself through extemporaneously playing his syrynx which Katin notes he always does with an intense grimace of fear. The Mouse’s developing self-understanding comes from struggling with Katin and ultimately becoming penetrated by Katin’s ideas.

One of the peaks of this comes when Van Ray gives the Mouse a drug called bliss. Uncharacteristically, he waxes loquacious on the beauty of his time as a 15 year old living on his own in Athens. During his monologue, he concedes that Katin is right about him. He admits that he plays his syrynx fiercely because he is terrified of the world.

Another peak comes during the denouement as Katin is in doubt about proceeding with his novel. The Mouse encourages him to push forward along lines Katin had proposed earlier in Nova that would make the Mouse the central figure in Katin’s novel. So the Mouse is able to speak of himself and situate himself in society, but only in the same terms a Harvard man does and under the influence of one of the wealthiest men in the galaxy. He can flip back and dialectically influence Katin, but only with Katin’s own ideas.

On some level, this process of self-discovery makes the Mouse a dynamic and deeply sympathetic character. On another, he can viewed as a cipher for Van Ray’s ambitions and Katin’s worldview.

Most recently I wrote: “The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester. . .is the spine of my developing-but-still-skeletal theory of proletarian science fiction. In the past, my description of this vein of science fiction has sometimes leaned a bit too heavily on something like a working class identity politics. More correctly, while the class origin origin of the protagonist, space sailor Gully Foyle, is a part of why I call this novel proletarian science fiction, the designation also has to do with the philosophical content of the novel. This includes but is probably not limited to: (1) the evolution of Foyle’s personal morality throughout his quest for revenge against a capitalist who wronged him; (2) Foyle’s attitude toward bourgeois society in general; and (3) Foyle’s ultimate attitude and actions toward the masses at the end the novel”

You got me thinking about Fred Pohl’s Gladiator at Law. When I reread it a few years back, it didn’t hold up as a novel, but my recollection is that it displays more class consciousness than anything else I can think of.

Nice to see the democratic socialist coming to the fore in the SF fan. You make me want to reread the Delany & Bester books. (Actually, not sure I’ve actually read the Bester one. It doesn’t seem to be in my collection. Delany has been one of my all-time favorite authors since the Ace Doubles version of “Empire Star” blew my teenage mind more than 55 years ago.)