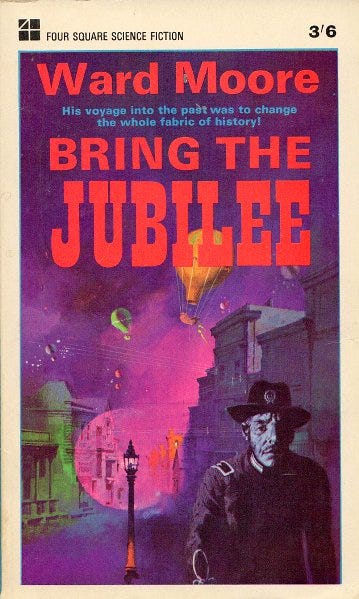

When I started reading Ward Moore’s 1953 alt history novel Bring the Jubilee I initially got pretty into it. The book is a “What if the South won the Civil War?” novel and from what I can tell an early entry in this subgenre. It’s about a young man coming of age in an economically and technologically backward rump United States. Unfortunately, the deeper I got into the book, the more I began to question whether the book had a point. Maybe that’s a funny approach to thinking about a novel but I am a funny little man who feels that science fiction and especially alt history should have some kind of point. As I continued reading, I determined Bring the Jubilee is mostly about a young man getting into a series of variously unsatisfying romances. There is other stuff in the book but that’s where the real meat is. My conclusory feeling was that the novel has an alt history setting but doesn’t particularly operate or succeed on the level of alt history.

Let me put forward a little hypothesis to try to prove my thesis. It seems to me alt history operates on the level of if X happened then Y would happen. That is to say it tackles that classic science fiction question, “What would happen if this goes on?” Like science fiction generally, alt history can do so on the level of technology and on the level of society. My hypothesis is one can tell any kind of story one wants with alt history but that the successful alt historian underpins their story with an emphasis on either technological extrapolation or sociological extrapolation. To build out this hypothesis I am going to take a non-exhaustive look at my previous readings in alt history. By showing how other books succeed, I hope to be able to show how Bring the Jubilee fails.1

Cherie Priest’s Clockwork Century series (2009-2015; Bone Shaker et seq.) represents one of my earlier forays into reading alt history. These novels have some politics but I don’t remember them as being particularly sociological. They were captivating because they used outre technologies and outre events to build out an interesting world and tell wild adventure stories. I hold that these books work as alt history on the level of technological extrapolation. They overwhelm the reader with dieselpunk imagery.

By contrast, Nisi Shawl’s novel Everfair (2016) and Terry Bisson’s novels Fire on the Mountain (1988) and Any Day Now (2012) work on the level of sociological extrapolation. Each of these books has a more-or-less strong political thesis. They are alt history with stakes. The point of Everfair is to imagine Black socialist self-government in Africa. The novel explicitly argues that well-meaning whites must give way to Black voices. The point of Fire on the Mountain is to take a balance sheet of the sacrifices and gains that would go into establishing a Black-led socialist society in what is now the American South. Any Day Now might be a little less pointed but it is still infused with Bisson’s particular revolutionary New Left politics. It imagines life in a counterculture commune as the Civil Rights era gives way to civil war and the United States in encircled by Mexican and Soviet revolutionary governments.

In these successful alt histories there are a broad range of kinds of stories told. The Clockwork Century novels and to a lesser extent Everfair are pure adventure stories. Fire on the Mountain does what might be called a standard Bisson maneuver of telling a mimetic story in a fantastic context. Any Day Now is mimetic to the point of feeling autobiographical.

It shouldn’t damn Bring the Jubilee that it’s a coming of age story and a kissing book. What I think damns it is that it doesn’t do enough with technology to be interesting or enough with society to have stakes or coherent politics. There are steam-powered cars, steerable balloons, gas lamps lit by telegraph wire, and more but one could remove any or all of these elements from the story and it would be just as interesting.

Now the book does do sociological speculation. It just doesn’t seem to be in any particular direction or have clear stakes. The United States is backwards and the Confederacy ascendant to the point of conquering South America. The United States has a different politics with different contours—pro-free trade, pro-foreign capital Whigs versus mildly developmentalist Populists—and an organization called the Grand Army is sort of a northern Ku Klux Klan without the Protestant trappings. The world wars take place without United States or Confederate involvement.

An interesting but underdeveloped point is that the United States is supposed to be more racist than the Confederacy because Americans blame their loss in the war on the Emancipation Proclamation. This is teased as an important thing. The protagonist Hodge’s family is ashamed that their Union soldier ancestor was an abolitionist. Hodge himself befriends a Haitian consul who, as an aside, Hodge learns is involved in assisting Blacks avoid deportation to Liberia and Sierra Leone by financing their escape to unconquered Native territory or to free Haiti instead. The book enervates itself by raising these issues and then not getting very close to them in its alt history analysis of “If X then Y.” The reader never learns what effect the Emancipation Proclamation—or, say, the Black population in the South walking off the plantations en masse and subsequent battlefield emancipation orders—actually had on the war in this timeline. The reader just knows Americans believe Blacks lost them the war. Is this run of the mill Yankee racism or a divergent timeline?

In fact, the alt history of the Civil War in Bring the Jubilee is paper thin and doesn’t get much play till the final section of the novel. Hodge becomes a historian in a utopian academic commune in Pennsylvania. There, Hodge’s sometimes lover Barbara, a physicist, develops a time machine that allows Hodge to travel back and witness the Union’s defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg, the defining moment of United States history that began the nation’s decline.

As you have probably guessed, Hodge unwittingly changes the timeline. It’s a small thing he does that distracts some Confederate scouts who were supposed to claim a position that would have won the battle for them, allowing the Union to claim the position instead. The incident also happens to kill off the founder of the utopian commune, who it so happens is also Barbara’s lineal ancestor. Thus the time machine was never created and Hodge is trapped in the new past.

And what are the stakes? Hodge, in the new timeline, speaks sympathetically of Reconstruction stating that the new world is more just than the one he left. However, he opines that the then-rumored deal between northern Republicans and southern Democrats to end Reconstruction would create a world just as unjust as the one from whence he came. This is fair editorializing on the part of Hodge (or perhaps I should say Moore) but would seem to indicate that there were no stakes to either side winning the Civil War. Is there a jubilee brought then?

There are elements of Bring the Jubilee as a kissing book that frustrated me as well. Barbara is a jealous and chaotic polyandrist and for most of their relationship Hodge exercises no agency. Hodge’s ultimate lover is a woman named Catty who is both mute and unable to understand speech when she falls for him. Things are left weird and unsettled with both women when he takes his trip to the past.

I see why this book isn’t a popular favorite or canonical must-read of 1950s American science fiction. I’m not sure who the current audience for it would be. Until its final chapters, it doesn’t have that granular focus on battlefield detail that Civil War dads crave. The scenery isn’t interesting enough for people who are into various -punk anachronisms. It’s likely too much of a kissing book for people who specialize in reading 1950s science fiction. And its stakes are too muddy for partisans of the right or left. I can tell Moore was an interesting guy from reading it but Bring the Jubilee is not a well constructed novel.

Now my big fat caveat here is that I’m not much of an alt history reader and with the exception of the book under review all of the alt history I have read has been fairly recent. There are big gaps in my alt history reading. I have never read L. Sprague de Camp’s classic Lest Darkness Fall. I have never read Harry Turtledove and have so far have not cultivated a desire to.

Philip K. Dick, The Man in the High Castle

Robert Harris, Fatherland

Michael Chabon, The Yiddish Police-Man's Union

Philip Roth, The Plot Against America

Ben H. Winters, Underground Airlines and Golden State

Colson Whitehead, Underground Railroad

Francis Spufford, Cahokia Jazz

Are all excellent books that deal with mostly but not entirely the sociological aspects you mention, and would be worth your time to read and compare.