Greetings and salutations! The topic of today’s issue of The Official William Emmons Books Newsletter is C. M. Kornbluth’s The Syndic. We’ll be looking at how this 1953 novel implicates ideas from politics, social science, philosophy and science fiction. Hopefully we’ll learn something!

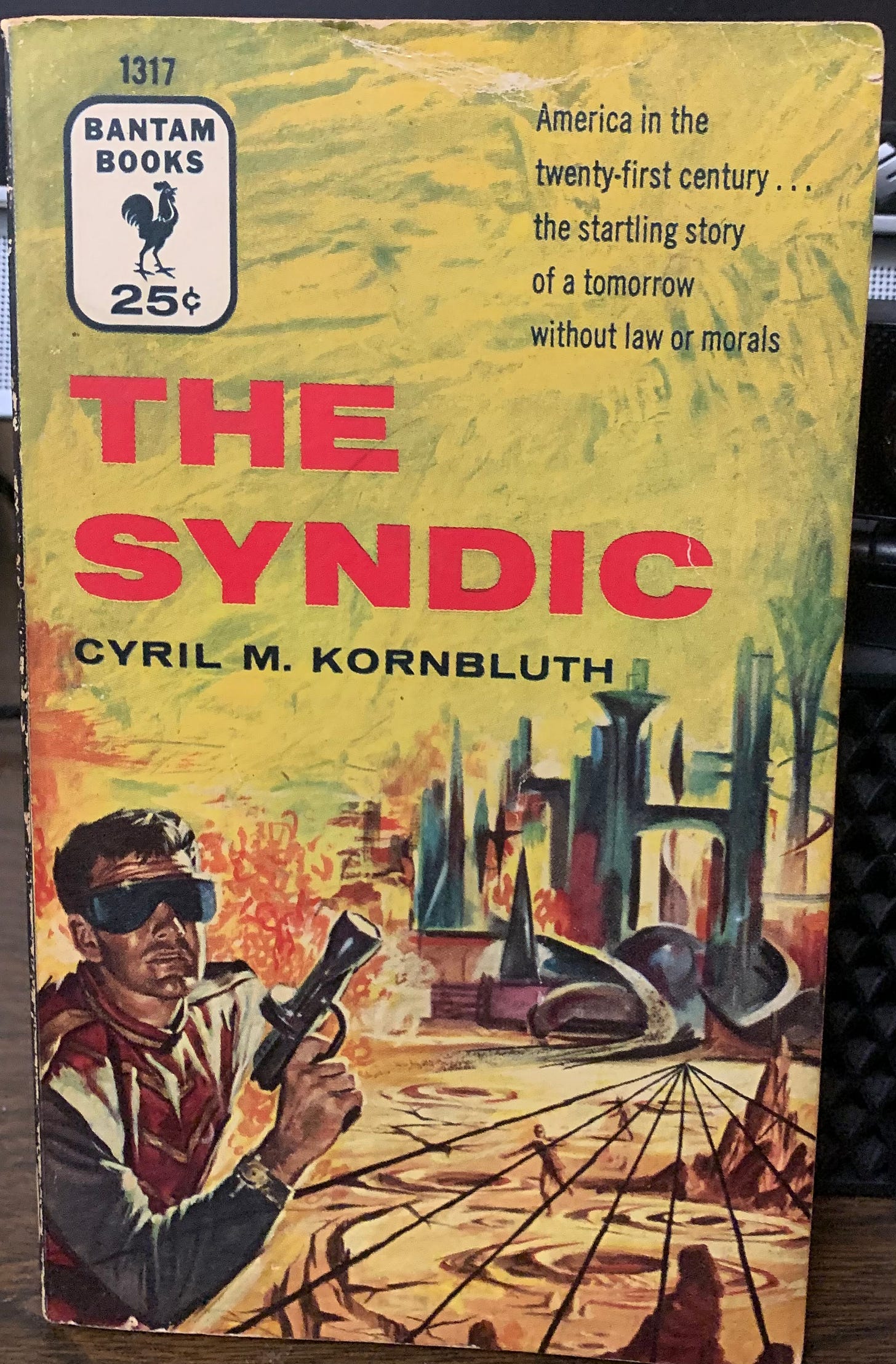

The Syndic by C. M. Kornbluth

The Syndic, which was serialized in the December 1953 and March 1954 issues of Science Fiction Adventures and which is available for free as an eBook from Project Gutenberg and as an audiobook from LibriVox, begins with some long quotes from fictional books. Most relevant to our purposes is F. W. Taylor’s Organization, Symbolism and Morale. The passage that stuck in my mind is as follows:

No accurate history of the future has ever been written—a fact which I think disposes of history's claim to rank as a science. Astronomers quail at the three-body problem and throw up their hands in surrender before the four-body problem. Any given moment in history is a problem of at least two billion bodies. Attempts at orderly abstraction of manipulable symbols from the realities of history seem to me doomed from the start. I can juggle mean rain-falls, car-loading curves, birth-rates and patent applications, but I cannot for the life of me fit the recurring facial carbuncles of Karl Marx into my manipulations—not even, though we know, well after the fact, that agonizing staphylococcus aureus infections behind that famous beard helped shape twentieth-century totalitarianism.

And so Kornbluth’s book begins not only with a shot across the bow of Marxism but a shot across the bow against positivism and any social science that uses a mathematical analysis of data as well. As a partisan of the notion that science can be used to extract meaning from human affairs, I was immediately interested. When C. M. Kornbluth comes for you, you pay attention.

Unfortunately, the novel as a novel is weak. Most of the good ideas and interesting plot points are clumped near the beginning and the final two-thirds mainly constitute a throwaway adventure. Fortunately, by today’s standards, novels were short back then. Still I walked away with one of my pet hypotheses reinforced—that the contemporary focus on novels to the exclusion of shorter forms is a mistake.*

Despite The Syndic’s weakness as a work of art, it is a successful medium for a handful of acerbic and brilliant bits. The novel presents positive idiosyncratic visions of the good society and the good life, an interesting take on the science of psychology, and negative critiques of positivism and Marxism that have implications not only for politics but for the science fiction field.

*It seems like there is something of a readership for contemporary SF/F magazines but my guess is it pales in comparison to the readership for books.

The Good Society: Putative Anarchy Under A Patriarchal, Libertine, Anti-Militarist, Informal Welfare State.

The Syndic is set in the future of an alternate history where following a social crisis in the first half of the 20th century, a coalition of two major criminal organizations overthrew and replaced the capital-G Government. In the West, there is the Mob. In the East, there is the titular Syndic.

The Syndic is patriarchal in the sense that its membership is composed almost exclusively of men, all of whom are related to its ruling Falcaro family. Gender roles seem more-or-less intact but nobody is neurotic about them.

The society the Syndic presides over is libertine—people, even children, have the right to gamble; promiscuity is normal and it is not unseemly for a man to proposition a woman; polygamy and polyandry among consenting adults are permissible; and drugs and alcohol are readily available. Despite the lingering threat of the old Government’s navy and saboteurs, the Syndic has no armed forces.

All the vestiges of capitalist society seem to be extant—banks, private employment, the police, money, the family, etc.—but the Syndic provides for the health and welfare of the people and regulates the economy. The Syndic manages free hospitals and a loose-fisted hardship fund. Near the top of the novel, F. W. Taylor, the Syndic’s chief ideologist whose views are expounded in the block quote above, reams out a banker for being too tight with credit. All such things are informal rather than regimented. The protagonist Charles Orsino is a low level Syndic member who accompanies police officers on their rounds and collects protection money from local businesses. This is how the Syndic funds itself in lieu of taxes. Orsino has leeway to collect less money from struggling businesses and dole out funds to particular police officers as he sees fit. The Syndic does not keep citizenship or population records.

Notably, Taylor would bristle at my characterization of the Syndic’s management of society as an informal welfare state. He insists, “The Syndic is not a government.” Instead, “The Syndic is an organization of high morale and easy-going, hedonistic personality.”

The idea of a happy and healthy society run by gangsters is, of course, a funny one. The story is too satirical to be a utopia and yet it is still a broadside against American society of the 1950s. Kornbluth was writing before the sexual revolution. Perhaps more strikingly, he was writing before the War on Poverty and the advent of Medicare and Medicaid. In the 1950s, something like a quarter of the population lived in poverty. Kornbluth presented a bunch of “easy-going, hedonistic” gangsters as being more effective at providing for the public welfare than the modern administrative state, which, in the early 1950s, was busy stockpiling atomic weapons and levelling Korea.

The Syndic on Psychology

Taylor’s ruthlessness toward the math-based social sciences is belied by the treatment of the science of psychology in the text, which is shown to have almost super-scientific potential and to be a strong social barometer. However, Kornbluth hoodwinks the reader to accomplish this.

Early in the narrative, the reader discovers that to the person of the Syndic’s era, the science of psychology is viewed as an antiquated superstition. The reader is given some background. At an earlier point in the history of the Syndic, different schools of psychology all disproved each other’s theories and none was left standing.

Unbeknownst to the public at large, the Falcaro family considered psychology to be too power to be allowed to die. Lee Falcaro, a rare woman involved in Syndic affairs, is this generation’s expert on psychology. It turns out she is into some MK Ultra kind of stuff.

The plot hinges on Lee Falcaro hypnotizing Orsino and rewriting a neurotic artificial personality onto him to make him an easy recruit for the Government. She proceeds to hypnotize herself in this way as well. The artificial personality only recedes when the subject of hypnosis takes the Government citizenship oath and then memory of their original self is restored without incident. This is the soft SF equivalent of super-science.

Of more interest to those of us who like to consider the Two Billion-Body Problem, Lee Falcaro explains to Orsino and Taylor that her secret research has uncovered that the old schools of psychology were right after all. She has uncovered all manner of neurotics and psychotics at large in society. She fears they may become a fifth column for the Government.

Taylor opines that both the earlier debunking psychologists and Lee Falcaro were right in their conclusions. In that previous generation, the Syndic’s society was vital and healthy and the neuroses and psychoses that accompanied Government civilization did not exist. Now, the Syndic’s society is in decline and creating maladjusted individuals.

Anti-Positivism: F. W. Taylor Contra Hari Seldon

Positivism is an orb science fiction enthusiasts should ponder because it seems to run parallel to at least some schools of thought associated with the genre. In relevant part, it is a philosophy of scientific progress that holds that the universe is ultimately knowable and that the scientific method should be applied to understand human behavior in the aggregate.

When I think about positivism, I think about psychohistory. Psychohistory is Isaac Asimov’s fictional science from Foundation. A skilled practitioner like Asimov’s hero Hari Seldon can solve the Two Billion-Body Problem on a galactic scale. He can chart and, as the leader of coordinated activities, direct the course of human events for a millennium—that is unless a single unpredictable mutant comes along and louses up his plans.

Foundation is science fiction’s ultimate positivist fantasy and Taylor is science fiction’s corrective anti-positivist iconoclast. For Seldon, it is the paramount responsibility of his followers to keep the flame of galactic civilization alive through a dark age. By contrast, in the introduction to The Syndic, Taylor is quoted,

Am I then saying that history, past and future, is unknowable; that we must blunder ahead in the dark without planning because no plan can possibly be accurate in prediction and useful in application? I am not. I am expressing my distaste for holders of extreme positions, for possessors of eternal truths, for keepers of the flame. Keepers of the flame have no trouble with the questions of ends and means which plague the rest of us. They are quite certain that their ends are good and that therefore choice of means is a trivial matter. The rest of us, far from certain that we have a general solution of the two-billion body problem that is history, are much more likely to ponder on our means…

This segues nicely into reading The Syndic as a critique of Marxism.

The Syndic: Dictatorship of the Lumpen Proletariat?

Without ever naming them, The Syndic takes aim at two doctrines of Marxism. These are the descriptive doctrine of dialectical materialism and the prescriptive doctrine of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Before proceeding, I’ll note Kornbluth would have been at least nominally versed in Marxism. While he was never in the Young Communist League like his friend and fellow Futurian Frederik Pohl, he certainly got drunk at their parties. Beyond this, Marxism was part of the intellectual firmament in the 1930s and 1940s and it would be hard for someone as thoughtful as Kornbluth not to have a basic grasp of it.

Dialectical materialism, simply put, is the idea that the driving force in social evolution comes from the contradictions in and among opposing social forces. The point of dialectical materialism is that it’s a tool for solving the Two Billion-Body Problem. When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called themselves scientific socialists and became partisans of the proletariat, it was because they used this tool and concluded that they should tie communism to the class that was apt to press the contradictions in capitalism to their ultimate conclusion. Scientific socialism constitutes sort of a psychohistory from below where every communist worker becomes a psychohistorian.

Taylor’s skepticism about answers to the Two Billion-Body Problem and antipathy for extreme positions implicitly critiques both dialectical materialism and its programmatic twin scientific socialism. Indeed, he calls Marx by name in the opening. The dialectical materialist conclusion that scientific socialism ought to hitch its wagon to the proletariat is also answered by the certainly satirical idea that only the criminal element has the vitality to overcome bourgeois civilization and build a different kind of society without poverty or neurosis. In countries like the United Kingdom and Ireland that had quashed their criminal element, the collapse of bourgeois society led to a general collapse of civilization. This could be construed as a jab at classical Marxism’s view that the criminal element, or lumpen proletariat, is politically unreliable because it is drawn from all classes and because it is imminently bribable.

The critique of the dictatorship of the proletariat is at once sharper and more ambivalent. In classical Marxism, the dictatorship of the proletariat is the democratic workers’ republic which consolidates proletarian political power and bridges the gap between capitalism and socialism by making despotic inroads against private property. Here we should note, Marx was a classicist and dictatorship was used in a Roman sense, rather than an etymologically modern one.

Then came the Soviet Union which was necessarily an armed camp. It was encircled by enemies and in its early days had to contend with invaders from 18 countries as well as counterrevolutionary armies associated with its own ancien régime. Measures which may have been appropriate as exigencies were raised to the level of political principles. This combined with a forced march toward economic modernization was the context in which Stalin’s crimes took place. This is what people are talking about when they talk about means and ends and socialism. For Taylor, this constitutes totalitarianism. And yet, it was the economically modern party-state USSR that crushed the Nazis.

In this context and in the context of the novel, Taylor’s answer to the problem of how to deal with external threats to Syndic territory is unsatisfying. He would simply let them come. His view is that militarism is corrosive to the kind of society the Syndic is striving for. If the society falls, so be it. They had a good run. Best to enjoy it while it lasts. Orsino and Lee Falcaro, who have been to enemy territory and know what is out there, are unconvinced by Taylor’s serene pacifism. Instead, their view is that the Syndic should raise an army and do something to deal with the growing population of neurotic and psychotic individuals.

The Good Life: Gather Ye Sense Impressions While Ye May

Naturally, Taylor refuses to assist Orsino and Lee Falcaro in their task of raising an army. He tells them that they are young people and that they should enjoy life instead of doing what they are setting out to do. He is aware his advice will not influence them. Still, he proffers the mantra, “Gather ye sense impressions while ye may.” His philosophical observation is that they will be old one day and they’ll want to be able to remember the good things in life. This, at least, seems sound.

Support This Newsletter!

NEW: I’ve instituted a virtual tip jar in the form of a Buy Me A Coffee account. This allows you to remit a small one-time payment to me if you like what I am doing here.

As always, I’d appreciate it if you’d peruse my eBay store. I’ve got some new items up including issues of Fantastic, F&SF, Galaxy, and If.

I also curate personalized bundles of vintage books and magazines based on your budget and interests. Some examples are in this post. Contact me if you are interested.

If you like this post, share it. Sharing is caring.