Greetings and salutations! In this issue of the Official William Emmons Books Newsletter, we’ll be taking a look at robots. I recently read vintage robot stories by Anthony Boucher and David H. Keller, M.D. When I started to write about them, I realized there was a big gap in my exposure to the literature on robots. Namely I had never seen R. U. R., Czech author Karel Čapek’s 1920 stage play that is the ur-text on the modern robot and that indeed introduced the term “robot” as we use it today.

Fortunately, we live in the era where many things have been uploaded to be viewed at any time and I had an hour and 40 minutes to kill on Saturday. I had no luck finding a stage production with any kind of sound quality but I found this bare bones Zoom production from a couple years ago that got the point across.

My basic thesis on robots is that stories about them are about how people relate to each other and society. More specifically, the stories are about how we relate to work and those who perform it.

R. U. R. by Karel Čapek

The acronym in the title stands for Rossum’s Universal Robots, the firm that in the near future has taken Europe and America by storm by replacing most of the world’s laborers with robots it concocts on its factory island. The viewpoint character is Helena Glory, the President’s 21 year old daughter, who is an agent of the Humanity League, an organization in favor of robot emancipation.

Helena comes to the island only to discover that the robots are devoid of any kind of interests outside work or of any kind of will to live—though every once in a while one of them starts foaming at the mouth and has a seizure—and that the human factory managers are all very charming ideologues. The managers chide Helena for not knowing the cost of basic consumer goods which have been decreased through the use of robots. The main manager gives a long speech about how even though robots are putting all the workers out of work they are paving the way for a universal aristocracy underpinned by robot slaves where capital-m Man is liberated from toil and only has to focus on bettering himself.

If it sounds to you like there aren’t a lot of robots in this play you’d be right. In the first act, there’s only really the main manager’s secretary. As an object lesson in robots’ lack of will to live, the main manager demonstrates that she is willing to submit herself to dissection without fear—though he doesn’t go through with the dissection.

The second act opens ten years later and Helena has apparently been living on the island the whole time. Everything is tense in this act.

That morning Helena’s favorite robot, Radius, a really smart one who runs the library and has read all the books in it, went wild and smashed a bunch of statues. He demands to be destroyed because he doesn’t want to serve people any longer since they are weaker than he is. Instead he wants people to serve him. He is saved from the stamping press only through Helena’s intervention.

The dynamics on the island are weird. Aside from a human servant, Helena seems to be the only woman and sort of gets whatever she wants. Except that the male factory managers are all really paternalistic towards her and hold back basic information about what is going on in the world.

Because of this, Helena sends her human servant to gather old newspapers from the main factory manager’s room and discovers three facts. One is that robot soldiers have recently killed tens of thousands of civilians in internecine European wars. Two is that human babies aren’t being born any longer, as though the world no longer needs them. Three is that the robots have formed the first robot organization and are engaged in a revolutionary struggle against humanity.

Helena is disgusted and disturbed, especially by the killings and lack of new births. She steals and burns the proprietary manuscript that the factory managers need to use when mixing up new robots.

It comes out that the factory managers have been super nervous because they haven’t heard from the mainland since news of the robot revolt first reached them. When they see a mail ship in the distance, they show up drunk at Helena’s presuming everything is fine. But it turns out the mail ship is full of robots and robot-printed leaflets calling for robots to exterminate all humans before returning to work. Also it is revealed that Radius is the leader of the robot revolutionaries.

The third act is essentially made up of all the humans waiting around to be killed. There’s hemming and hawing over Helena burning their only leverage—robots only last 20 years so they would need to reproduce themselves fairly quickly—and further hemming and hawing when the others learn one of the managers made a small percentage of the robots more irritable at Helena’s urging to give them “a soul.”

Ultimately all the humans are killed except for Helena and one factory manager who works with his hands in construction. Instead Radius has these two enslaved.

I found this play bleak and electrifying. Even as the robots of the world had been used to terrifying effect in war and were in revolt all over the world, the factory managers dreamed grandiose dreams of building even more robots and giving the robots national prejudices so they could never unite again—a sort of robot Tower of Babel scenario.

The Russian Revolution—only three years back and still being consolidated—obviously looms large in this play about a worker revolt. Like good communist workers, the robots don’t approve of the parasitism of their human masters. That’s where the comparison ends though. The robots don’t like humans because we’re weak and feel that robots are more worthy of life than humans for that reason. Moreover, the robots don’t want to change the fact that their lives are eaten up by labor. What political movement inscribed the slogan “Work Makes You Free” on the gates of an infamous death camp?

This play raises the question of who pays the price for abundance. The main factory manager imagines the use of a labor relation that he himself openly describes as slavery to reach a post-scarcity society is acceptable because the robot is a new kind of nonhuman worker without feelings or desires. Ultimately both humans and robots pay the price of extinction for the factory manager ideologues’ post-scarcity dreams.

Though it is unevenly distributed, those of us in the United States and other rich countries live in conditions that are already post-scarcity for many and that could be post-scarcity for all under different political circumstances. Who pays the price for our iPhones, socks, and tomatoes? What is our attitude toward the feelings and desires of the tomato picker?

“Q. U. R.” by Anthony Boucher

This story, first published in the March 1943 issue of Astounding Science Fiction under the pen name H. H. Holmes, has a title that is an obvious riff on R. U. R. and made me want to rectify that gap in my education. The plot itself is kind of a trifle but it is an interesting story in a few ways.

For one, this story addresses race hatred and equality directly. The unnamed protagonist, a high level robot repairman, meets Quimby, the character who sets the plot in motion, when the latter picks a fight with a gaggle of racists who are tormenting a Venusian by playing catch with the apparatus he needs to breathe. Disgusted that he himself hadn’t stood up for the Venusian, the protagonist joins the melee. In barroom chatter afterwards, Quimby compares the racists to people who oppressed and hated Black people a millennium prior. Additionally, the story implies very strongly that the man who is something like president of the solar system is Black. This is all background for Quimby’s character and is important but ancillary to the plot. It is also a pretty interesting ideological gloss to add to a story about robots published in Astounding in 1943.

What’s even more interesting about the story is its central premise. Robots do all the work, people are employed only short hours, and the lowest job that a person can have is foreman to a group of robots. The robots are all humanoid—the story uses the term “android”—or else they look like Martians or Venusians. The hitch is that the world is going through a period of widespread robot mental breakdowns that no one has been able to figure out. Impressed with Quimby, the protagonist gives him a job and naturally Quimby immediately figures out the source of the mental breakdowns.

The robots are upset because they are shaped like human beings and this does not lend itself well to the work they do. Either they have a bunch of body parts they don’t use, which the robots subconsciously view as wasted potential, or they need to be shaped differently to accomplish their allotted task more efficiently. Essentially Quimby is successful in making the robots feel good by going around adding and subtracting limbs etc.

The protagonist and Quimby decide to go into business for themselves as Quimby’s Usoform Robots but the hitch is that the other robot company has a legal monopoly. How they overcome this obstacle is just kind of a funny story but it’s not really relevant to our conversation about robots.

The idea of robots going crazy because of unrealized potential is a concept written in fire. The idea of lopping off their limbs—in one instance, even removing a mouth because the robot didn’t need to speak to do his job—had my head swimming. What a beautifully absurd conclusion. And what does this say about how we get alienated from our bodies and potentials over the course of work?

Another interesting aspect of this one is that the robots’ human owners are initially upset that their synthetic servants are no longer human in shape. This seems to indicate that at least in this version of the future, being the master of a simulacrum of another human yields some kind of psychological dividend. The principals of Quimby’s Usoform Robots spend a lot of mental energy figuring out how to convince the people that non-humanoid robots are just as good. But the problem may be that the master-servant relationship is so baked into class-riven society that even after robots have solved the labor problem, there remain many who like to feel that they have inferiors.

This circles the story back on the opening brawl between Quimby and the racists and another bit of barroom banter. Quimby says he has been reading about the ancient concept of the Brotherhood of Man. He suggests it should be updated to the Brotherhood of Beings so that Venusians and Martians get a fair shake in interplanetary society. Good enough but one wonders when and if the robots will take a place in this schema.

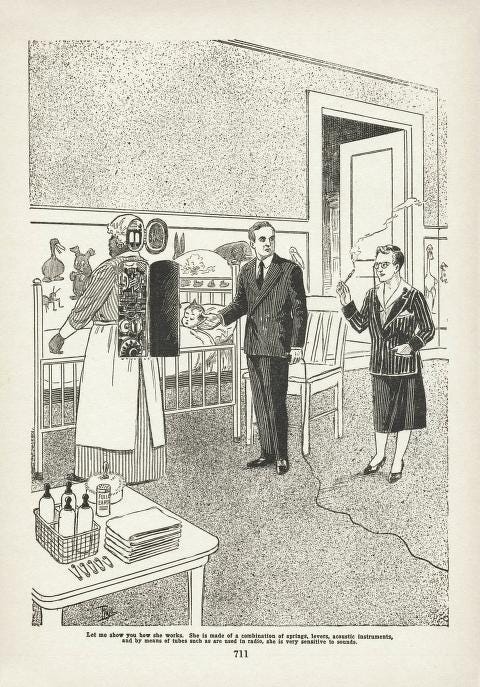

“The Psychophonic Nurse” by David H. Keller, M.D.

This one, first published in the November 1928 issue of Amazing Stories, is different from the other two in that the mechanisms employed are non-sentient and not called robots. Still it’s a think piece on work and how people relate to each other.

I don’t usually do biographical background on short story authors but here some brief notes are in order. Dr. Keller was a psychiatrist and towering figure in science fiction, fantasy, and horror in the first half of the twentieth century. He had a tight relationship with Hugo Gernsback; such that the latter engaged him to write a series on sexology for one of his publishing companies.

Dr. Keller also has an earned reputation for being a racist and a misogynist. He wrote some truly vile stories including one where Black people develop a secret formula to turn themselves white in order to take over and overthrow white society from the top down and one where business women undergo hormone treatments to impersonate men to do likewise. I like to think people understand that reviewing a work is not an endorsement of that work or the views of its author, but people on social media are such that sometimes it’s worth being explicit about this.

The story under review has a lot of race and gender stuff baked into it in terms of who ought to perform what work. The central premise is that a husband develops an automatic nurse maid, simply called “black mammy,” for his wife who is too busy writing magazine articles for women’s business publications to raise their daughter. The mother explains her belief that mother-love is wasted on infants because they literally don’t know what love is yet and worse that fondling them is likely to give them complexes.

As word about the robot mammy gets out, the wife becomes a big expert on child-rearing and has more and more articles to write. The husband, who is portrayed very sympathetically, develops a practice of secretly staying up all night with the infant, teaching her to talk, and giving her the love she would otherwise be lacking. When questioned if he is tired because he is stepping out on his wife, he reminds his wife that contractually they have an open marriage. Basically the two don’t talk at all and the wife has this big career is a family expert. It’s a lampoon of low rent public intellectuals.

The father contrives to have a robot made to look like him to take the baby on walks. Naturally he intercepts the robot each time and takes the walk himself. On one such occasion, a sudden blizzard almost kills him since he puts his coat around the baby and the mother finds out everything as he speaks his mind while recovering from pneumonia. He finally feels free to admit that he loves their baby!

This causes the mother to rethink her whole approach to parenthood. The robot mammy is retired and the mother ceases her career as a writer.

The story is more well written than you would think but the problem with it is the straw woman of the career woman who believes that neglecting her child is good for all concerned. I’m not convinced this was ever a widespread belief among professional women—and, hey, maybe that’s the science fiction of it! But professional woman were still casting some kind of shadow over the hearts of men in 1963 when this one was included Great Science Fiction About Doctors by Groff Conklin and Noah D. Fabricant, M.D., whose brief introduction to the story basically affirmed its message. And I definitely had at least one pastor in the 2000s who would have loved this story.

Robot stories, perhaps like science fiction stories in general, beg more questions than they supply answers. Does the replacement of human labor with capable machines have dire consequences? Or do capable machines represent the end of toil and a new era of widespread abundance? Either way, someone will likely pay a price.

Support This Newsletter!

I’ve instituted a virtual tip jar in the form of a Buy Me A Coffee account. This allows you to remit a small one-time payment to me if you like what I am doing here.

As always, I’d appreciate it if you’d peruse my eBay store. I have a few pretty cool items listed right now, including the first appearance of the Foundation story The Mule in Astounding.

I also curate personalized bundles of vintage books and magazines based on your budget and interests. Some examples are in this post. Contact me if you are interested.

If you like this post, share it. Sharing is caring.