Forgive me, readers, for I have sinned. It has been four months since my last Astounding Science Fiction read through post. Today I’ll just be dealing with a single novelette featured in the December 1949 issue of Astounding because I ended up on a tangent about the treatment of women and girls in early American magazine science fiction. The plan is to return to this issue and cover the rest of the material in it near the beginning of next week.

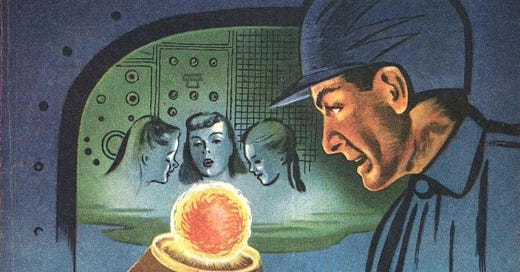

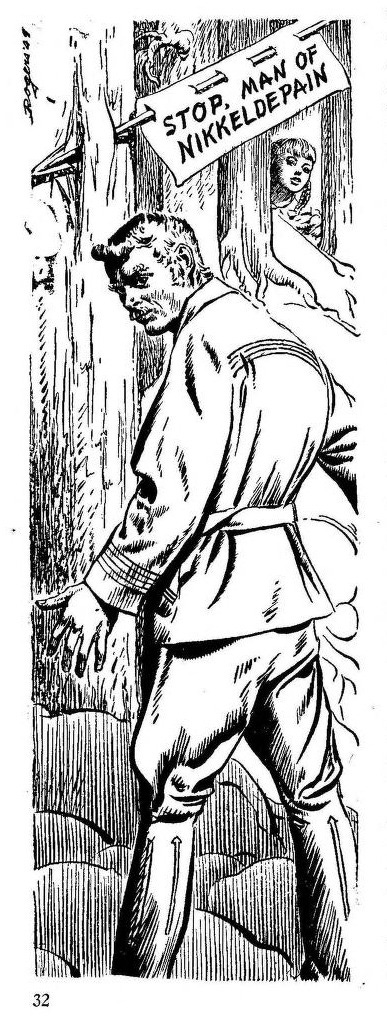

“The Witches of Karres” by James H. Schmitz

“The Witches of Karres” is about a man’s life-changing encounter with three uncanny girls. I’m going to come at it sideways.

I’ll start with the caveat that I try to avoid, “Isn’t it something how fucked up these guys were back in the day?” kind of posts because they’re generally boring to me and frequently miss other things going on. For good or ill, that’s the kind of post this one has turned into.

Thinking back on my readings over the past year—mostly from American science fiction magazines from the 1950s or before—I’m struck by the dearth of women and girls who were fully realized characters. This is certainly related to male chauvinism in an area of literature that was at the time primarily by and for men. Still we’d be remiss not to note a dearth of fully realized characters in general. And we’d be even more remiss if we held that his broader context of thin characters absolved the genre of its weird stance toward women.

There was definitely something weird going on with women and girls. For example, take the 1932 classic “The Last Woman” by Thomas S. Gardner (misattributed in its debut in Wonder Stories to Thomas D. Gardner). In that story, men live in a post-emotional society that has evolved beyond a need for women. Now the story doesn’t portray this as a good thing. The hero is a spaceman who hasn’t had his anti-emotion chemicals and falls for the titular last woman, an accidentally created person who is kept around as a museum piece.

Despite her eponymous status, the last woman is not particularly well developed. My contention is that the story’s very existence betrays bizarre attitudes and deeply felt discomfort toward women—if not on the part of the author then at least on the part of science fiction community. Ideas don’t come from nowhere.

So stories with fairly normal attitudes towards women and fully realized characters who are women or girls do stand out. In my personal readings, the dynamic woman doctor in the medical thriller “Contagion” by Katherine MacLean and the telekinetic girl in More Than Human by Theodore Sturgeon come to mind.

The above are both examples whose ultimate origin is Galaxy Science Fiction. I have been saving in my back pocket for just this occasion two other examples of stories about women from the December 1950 issue of that publication. They are “The Second Night of Summer” also by Schmitz and “Jaywalker” by Ross Rocklynne.

“The Second Night of Summer,” is set on an idyllic agrarian planet in a broader human galaxy. It is about the relationship between a boy and a grandmotherly traveling patent medicine saleswoman. The woman is some kind of galactic secret agent and she needs the boy’s sharper reflexes to head off an alien invasion. The woman’s motivations are both complex and discernible and the story reflects a normal attitude towards women.

It contrasts sharply with “Jaywalker,” which is a pure quill science fiction story characterized by bad science and a main character who is jealous and stupid. She heedlessly risks her life and that of her unborn child to make her space pilot husband prove he loves her. For the story to work, Rocklynne invents a fictional regime of space medicine wherein if a woman is pregnant in zero g then she and her fetus will die violently. Despite this being common knowledge in the world of the story, the protagonist boards her husband’s passenger spaceship with false credentials so she can surprise him with the news that she is pregnant. The main body of the story is made up of a nasty girl fight between the protagonist and her husband’s flight attendant (in today’s lingo, “work wife”) in which the protagonist is shamed and humiliated.

All of this is preamble to say I was curious and optimistic to take a crack at “The Witches of Karres” on the level of this “woman question” because of my past experience with Schmitz. I will admit to fearing its potential to be an overly long novelette about psi powers given its appearance in John W. Campbell, Jr.’s Astounding.

I was sort of right all around. “The Witches of Karres” is a long novelette about psi powers. The girl characters in the story are fully realized. That said, there is also something weird going on in this story between the man and the girls.

The protagonist Captain Pausert is a young space trader from the planet Nikkeldepain. He is traveling the space ways, trying to climb out of debt and impress his fiancée’s wealthy father. He is good at convincing people to buy stuff from him and things are going well until he finds himself on the backward planet Porlumma. Barely avoiding a barfight arising from competing planetary chauvinisms, he ends up wandering around and getting lost.

While lost, Pausert gets in an altercation with a baker because the latter is threatening an enslaved teen girl named Maleen from the strange planet Karres. The cops get involved. Pausert is forced to make restitution to the baker and purchase Maleen if he wants to avoid a lengthy jail sentence. He promises to emancipate and repatriate Maleen to Karres and in the course of placating her agrees to purchase and emancipate her younger sisters the Leewit and Goth.

All the girls have different psi powers. Maleen has limited precognitive ability and seems to be nursing a crush on Pausert. The Leewit, the middle sister, has psychokinetic powers and a poor attitude. Goth, the youngest sister, has the ability to teleport and is the most uncanny and witch-like. They also have the ability to propel Pausert’s ship through interstellar space near instantaneously for a limited amounted of time using a psi power call the Sheewash Drive.

After some misadventures, Pausert brings the girls back to Karres, a mostly uninhabited planet where everyone is a witch and most people live a big town hidden from aerial view by the forest canopy. Pausert falls under the spell of the planet and spends weeks living in the sisters’ house smoking a pipe and drinking hot beverages provided to him by their mother. This seems to be semi-unconscious on his part and it turns out it is part of a test the witches are putting him through.

The witches load Pausert’s ship down with a lot of foods and other natural goods. He is grateful though he knows galactic import-export regulations prevent the trafficking in such goods. Before he leaves, Maleen expresses that she will be of marriageable age very soon. He also has an encounter with Goth where she shoots an arrow over his head to say goodbye. He admires her uncanny wildness.

When he attempts to return to Nikkeldepain his misadventures catch up with him and his ship is boarded by his would be father-in-law, some space cops, and his fiancée. It turns out the latter is no longer his fiancée and that she has married another, much wealthier man. Rather than submitting to arrest, Pausert forces the party off his ship at gunpoint. He decides to return to Karres.

It seems like he won’t be able to escape additional pursuers from Nikkeldepain when all of a sudden the Sheewash Drive kicks in. It turns out that Goth, as part of an approved plan by the witches of Karres, has stowed away on his ship.

Maleen’s expression of attraction to Pausert was just a feint to interest him in returning to Karres. He was actually being set up to become betrothed to Goth. It so happens that the witches are using the Sheewash Drive to move their planet to protect it from outsiders. Pausert and Goth can only rejoin them once he has studied the ways of the witches. Pausert agrees to become Goth’s husband when she grows up and Goth, in turn, agrees to be adopted by Pausert during the remainder of her childhood.

It is a weird ending! I do not like it! She’s young enough that’s he’s like oh let me adopt you now and later we’ll get married and I really appreciate how you are a wild and free witch girl. Now if we can put aside this poison pill, it’s otherwise fine. It’s light hearted space opera. Nothing to write home about but charmingly inoffensive—until it isn’t.

Isn’t it something how fucked up these guys were back in the day?