1950s Short Fiction & Mid-Year Housekeeping

Reviews Of Robert Abernathy, Brian W. Aldiss And More

Greetings and salutations and a special welcome to all the new subscribers who have signed up since Sunday. This installment of the Official William Emmons Books Newsletter is about cleaning and organizing house in a couple of senses. First, I’m going to be reviewing a handful of 1950s short fiction I’ve read over the past few weeks that I haven’t had space for in the newsletter up till now. Second, since the newsletter has evolved so much over the past few months, I’m going to take the opportunity to lay out what it is I’m trying to accomplish here.

Reading Diary: Here Come The Also Rans

In addition to my deep dives into the big three 1950s science fiction magazines—Astounding, F&SF and Galaxy—I’m reading a smattering of issues of other science fiction magazines from that decade that did not achieve the same level of prominence. This has already proved to be rewarding, as I enjoyed reading and reviewing some stories out of Venture and Imagination last month.

From If: Worlds of Science Fiction: H. B. Fyfe and Robert Abernathy

In my business as a bookseller, I acquire a lot of old magazines and I have sort of a system for what I sell and what I hold onto for personal use. In general, I sell everything from 1960 forward unless it is If. For that magazine, I’m trying to collect the issues Galaxy published so I tend to keep the later ones and sell the ones from the 1950s. But when a digest-sized 1957 anthology titled The First World of If crossed my desk, I thought here’s my chance to get a sampling of the earlier stuff. These were the first two stories.

“Let There Be Light” by H. B. Fyfe

First published in the November 1952 issue of If, this is a short-short post-apocalyptic one where a group of men cut down a tree to block a still extant highway so that a crew of robots from the old society will come out to remove the tree. The men capture and destroy one of the robots so their village can use its oil for lamps. The story was workmanlike and didn’t have any real defects but I had forgot I read it until I was looking at the table of contents of The First Worlds of If in preparation for this post.

“The Rotifers” by Robert Abernathy

I had never heard of rotifers until I read this story first published in the March 1953 issue of If. Apparently, they are microscopic aquatic animals. This story is about a young boy who becomes obsessed with them when his father buys him a fancy microscope and the pair bring in some pond water to look at.

The child loses interest in going outside to play baseball with his friends and spends all his time looking into the fish bowl of pond water. The boy becomes withdrawn. Where before he would ask his father to come look into the microscope to see what he had seen, he comes to stare ceaselessly. The boy’s mother is very upset by all this.

Eventually, the father intervenes and asks to take a look and a rotifer seems to approach the wide end of the microscope and stare back. When the father asks the son why he spends so much time at the microscope, the boy explains that the rotifers live very fast and he doesn’t want to miss anything.

Things come to a head when the boy becomes sick. He explains to his father that the rotifers perceived him by looking back up through the microscope. Somehow, the rotifers established contact and the boy learned they never knew about humanity before and hate the idea of sharing the planet with another intelligent species. The rotifers’ goal is to commit universal genocide using new bacteria they’ve bred. The rotifers don’t fear death because their offspring are born knowing everything they know and their eggs can survive being dried up. When the boy refused to return them to the pond so they could rouse their fellows to a war of extermination, they made the boy ill. Not understanding any of this, the mother had already poured the rotifers back in the pond.

Trying to comfort himself that his son was just raving because of his feverish state, the father goes out to the pond. There is a new miasma coming off of it. The father becomes afraid.

I found this story well-written and affective. Abernathy did a good job conveying an aura of domesticity belied by horror. In terms of where this falls in the history of science fiction, this felt like a different take on what Theodore Sturgeon was trying to do in his famous 1941 novelette “Microcosmic God.”

From Future Science Fiction: “Safety Valve” by Brian W. Aldiss

This one from the August 1959 issue of Future (no scan) was a random pick. When I can find them cheap, I collect bound volumes of science fiction magazines. A seller on eBay had three issues of Future bound for a low price and this was the first story out of those bound magazines.

“Safety Valve” was a disappointment. I thought it might be good because Aldiss has such a strong reputation in science fiction. I’m also interested in the editor of Future at the time, Robert A. W. Lowndes, who had been a Futurian and had become Episcopalian to such an extent that he added the “A.” to his name for Augustine. For whatever reason, Aldiss wasn’t sending Future his best in 1959.

I think there are three basic problems with this story. One, it is is a psi powers story. Psi powers stories don’t have to be bad but they do have to be well-executed and/or have something else going on to be successful. For example, I reviewed “Defense Mechanism” by Katherine MacLean in the previous installment of this newsletter and it worked because it was tightly written. More famously, The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester is a philosophical tour de force about human potential, class and social responsibility in which everyone has developed the psi power of teleportation. The story under review isn’t well-executed and doesn’t have anything else worth doing going on. Two, a major reason “Safety Valve” is not well-executed is that the story hinges on the narrative having telegraphed that the protagonist Dashiell Whitely is a serial killer by the end of the story and Aldiss is unsuccessful in so doing. Three, the story is too long.

The plot is simple enough. Whitely is a bored civil servant. One evening when he is showering his apartment is invaded by Herb Farthingdale. Farthingdale goes straight into Whitely’s bathroom and begins addressing him.

In the back and forth that follows, it comes out that Farthingdale, who seems old before his time, went to college with Whitely but Whitely doesn’t really remember him because Farthingdale is an introvert. Farthingdale’s goal is to get Whitely to come with him to a second location and out of boredom Whitely agrees.

A chauffeur drives them to a government nuclear compound. On the way, Farthingdale explains that boredom is the key driver in human civilization. When they get to the compound, Farthingdale takes Whitely into a subterranean facility unrelated to the nuclear project but which is protected by the same set of guards.

In essence, Farthingdale is over a government project where men sign away years of their lives to sit around with nothing to do until they develop their latent potential to become psychokinetic out of boredom. By the end of their contracts, the men always choose to stay on indefinitely because they are introverts and come to like the life of total isolation.

While you may think Farthingdale has trapped Whitely to get him into the project, in fact, the outcome is more sinister. The men in the project need some kind of outlet, so once a year they are allowed to murder someone as a group. It is always a bad person the law can’t otherwise get. Since Whitely is a serial killer, he is a natural candidate.

Somehow this takes 22 pages. I don’t even have a huge problem with the premise of a government project where boredom is used to goad people into becoming psychokinetic. I just feel like it could have been done in 10 or 15 pages and I’m still at a loss as to why the annual murder keeps morale up.

From Fantastic: “Wonder Child” by Joseph Shallit

According to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, when the editor of Ziff-Davis’ Amazing Stories magazine Howard Browne launched Fantastic in 1952, the idea was to have a magazine with an appeal broader than that of the by-then down market science fiction magazine Amazing. Until after 1953, Fantastic published some famous bylines from outside of science fiction. The story under review, first published in the January-February 1953 issue, comes from this period but my 2024 eyes are unable to tell the extent to which Joseph Shallit or some others listed in the table of contents might have been a draw to the general reader in 1953. A little author bio on the inside cover announces that Shallit was a newspaper man who had at the time recently published his fourth mystery novel. It seems like this issue’s big selling point was supposed to have been a “masterpiece” somehow co-written by Edgar Allan Poe and Robert Bloch.

Approaching this story made me realize what a big factor name recognition is in my reading of old science fiction. In my head, I have an under-considered list of perhaps a few dozen authors from this era whose names I recognize as some kind of sign that I’m getting into something good. As my experience with Aldiss’ “Safety Valve” shows, this prejudicial mentality is foolish.

Anyhow, Shallit’s not on the list and I don’t have an immediate positive association with Ziff-Davis publications. So when the going got a little tough at the beginning of this story, I was tempted to DNF the story. I’m glad I stuck with it. It was good!

Why did I have a problem at the top of the story? Well, it opens with a childless bohemian couple in their 30s in couple’s counseling. We’re not told why they’re seeing a psychologist. We just get their psychologist striving intensely to talk them into having a baby before its too late. It hit a little too close to home because I am part of a late 30s bohemian childless couple and my partner is a therapist. I found the psychologist’s lack of professionalism jarring. Of course, it comes out that he is a mad scientist, so what can you expect of him?

The couple turns on a dime and goes from total agreement that neither of them want a baby because it will interfere with their careers in the arts to total agreement that they both have wanted a baby all along. The psychologist creates the conditions for this sea change when he shows them a machine he has invented called the Maturator which stimulates a fetus’ or infant’s nerves to grow and develop more quickly. This allows the baby to fend for himself sooner, leaving mom and dad time to paint and write respectively.

But the process works too well and the neighbors can sense there is something weird going on. They develop the idea that the bohemians’ infant died and that they adopted an older child which they are trying to pass off as an infant. When it comes time to socialize the child, the neighbors keep their kids away.

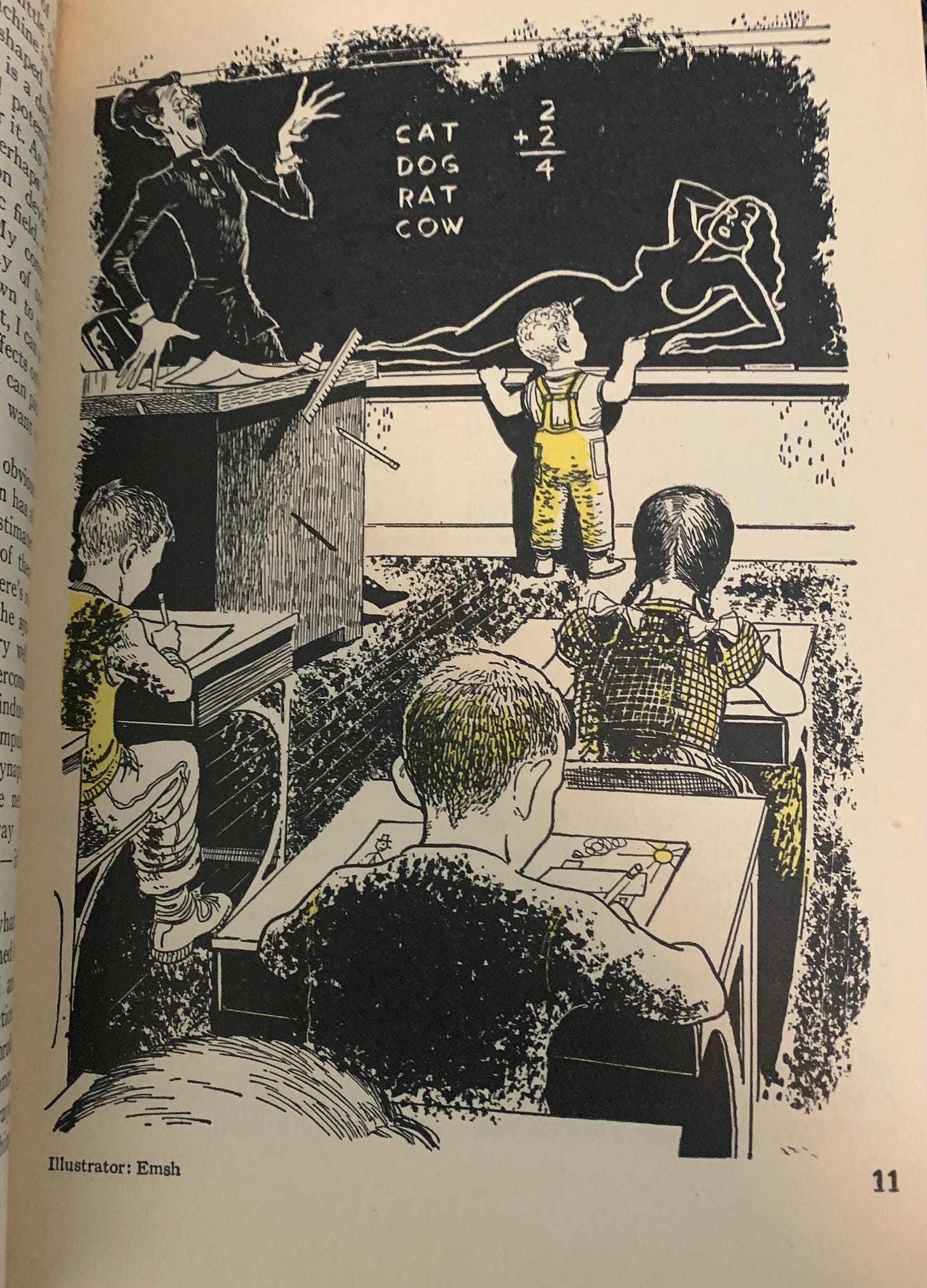

So the bohemians enroll their one year old in a day care program for three year olds and because of his advanced skills he gets bumped up to an art class for five year olds. But he gets himself expelled by drawing pictures of his parents naked and asking questions of a sexual nature during story time.

The child is by then a bibliomaniac and spends all his time reading and asking his father obnoxious questions with trick answers. In order to use up his son’s energy, the father gets the boy—who I think is maybe toddler age at this point—onto a TV quiz show. He’s an instant star and he gets put on other TV shows as well. The father quits writing in favor of managing his famous son’s career.

Socialization gets harder and harder and the child runs through friends very quickly as he matures, so ultimately the father has to hire boys from a talent agency to be his friends. Even this proves futile, as the child becomes competitive and violent. He breaks an older boy’s arm over a dispute about whose turn it is at bat when playing baseball. By age five, he is a distant and alien creature.

The psychologist insists that the boy’s competitiveness is a good thing and only means that he is prepared to live in the future. The psychologist says he has mapped the course of society and that it is headed to a very competitive place. For this reason, the Maturator was attuned to stimulate the hypothalamus at the expense of the prefrontal cortex so that the child would be less restrained.

On the child’s sixth birthday, the father is at his wit’s end with his son’s behavior and enters the psychologist’s office demanding to see the notes on the project. He obtains them after a physical struggle with the psychologist and discovers the psychologist’s conclusion that by age six the child will be physically and emotionally prepared to kill his parents. The father reacts by planning to poison the son’s birthday cake but when he gets home he hears his wife scream.

By the end of this one, the suspense had me and I loved the dark ending. And come to think of it, the psychologist was right in the sense that we live in a more competitive society today than they did in 1952. I recommend reading this one.

Mid-Year Housekeeping: What Are We Doing Here?

I started this newsletter back in March as a mere marketing tool for my business as a bookseller, thus the name William Emmons Books. Since then it has evolved into an outlet for me reflect on and theorize about my readings in old science fiction and fantasy. I think these two purposes work together—I am trying to show what a rich and fruitful hobby reading and collecting old science fiction and fantasy can be.

I’ve never really laid out the parameters of what I’m trying to read and why. Moreover, my ideas about the business side of things have evolved enough that I’ve deleted and edited some older posts that don’t reflect my current business model. It’s worth putting out there what I think I’m trying to do now. I’m still very new at this and my are subject to change.

What I Am Reading and Reviewing and Why

My main interest is in science fiction. I entered 2024 with the goal of getting a 30,000 foot view of the genre. My plan was to read classics as well as contemporary texts and, because I am overly ambitious, to also dabble in crime fiction. It quickly became apparent to me that my interest in the old stuff was so strong that my plans to read newer science fiction or crime fiction needed to be shelved.

As my reading plan evolved, I cut myself off in principle around 1980. In practice, I’ve cut myself off sometime around 1960. At some point, I stopped thinking in terms of “classics.” I’ve also determined that I have to read fantasy too in order to understand science fiction.

When I started out in my reading plan, I was mostly reading anthologies and was covering the whole period from 1926 to 1960. Sometime since starting this newsletter, I’ve become especially interested in the 1950s and reading whole magazines.

Off hand, I can think of four reasons why I’m reading interested in old science fiction. One is summed up by something I read last year by Eleanor Arnason that has stuck with me:

To me, living in the strange postwar world of suburban consumerism, science fiction was realistic. Official life—what I saw on TV—was domestic and comfortable. Ozzie and Harriet and Father Knows Best. But the same world contained fallout shelters and witch hunters. It was an eerie combination.

By contrast, the science fiction magazines were full of stories about radioactive wastelands and police states; mutants, both good and bad; and the hope of space. It gave me a world I recognized, and it gave me hope. It had a huge, important message: change is possible and inevitable. We would not be stuck in the 1950s forever.

My personal experience is that American life is still basically insane. It’s more on the official surface now, of course. I like the idea of science fiction as something that stands on the periphery of society and reflects something real about what is going on. At its best, science fiction is prophetic, not in the sense of mere prognostication but in the sense of a jeremiad.

Second, I like science fiction because I have a bit of the old Gernsbackian ideology of scientific progress in me. You kind of have to let go of the fascination with gadgetry and turn it on its head and ask questions like, “Who is this scientific progress for?” But I think it is good to think of the universe as ultimately knowable and to think that problems can be solved.

Next, I like old science fiction in particular because you get to read it in historical context. It’s an interesting way to touch the past.

Finally, and I cannot stress this enough, I think it’s neat.

My Business as a Bookseller

I currently have a three part business model as a bookseller:

(1) I list books and magazines for sale on eBay. I currently have only 58 items listed—SF/F of course but also other items from paranormal stuff to Westerns. Last month it was difficult to get new items listed for various reasons. I hope to do better this month.

(2) I curate personalized bundles of books and magazines. This has gone through a couple iterations but the main thing is I put together something based on your interests and budget. This post has some examples. If you’re interested in one of these contact me.

(3) I table at public events. These are mostly in Kentucky but I will be at PulpFest outside Pittsburgh, Aug. 1-4.

If you like my writing, engaging with my business as a bookseller would be much appreciated.

I like your blog, William, and also this passage: "I’ve also determined that I have to read fantasy too in order to understand science fiction." I love both science fiction and fantasy, and think of science fiction as a branch of fantastic literature. (I think Robert Silverberg put it this way.)